Key Takeaways:#

China’s middle-class expansion, the US economic rebound, European consumers feeling the pinch: surely, affordable luxury is poised for superior growth? I don’t think so.

In handbags, the market is crowded and the more premium brands are better capturing the cultural zeitgeist, generating better growth.

Jewelry and ready-to-wear are likely better segments to roll out an affordable proposition

The growing potential#

The affordable luxury segment should be driven by value-for-money American consumers and aspirational Chinese consumers who are just entering the sector. The US is the land of the deal. It’s the country that invented Walmart, Amazon, eBay, refillable Coke, couponing, all-you-can-eat menus, outlet malls, the doggie bag, buy one, get one free, and so much more. So presumably, affordable luxury should resonate well there. In the decade between 2000 and 2010, the US saw a rise of the affluent, with more people becoming wealthier and the middle class getting more money to spend. In 2019, consumer confidence was very high, and the unemployment rate in the US was at the lowest it had been in fifty years, and there are now hopes for a post-COVID rebound.

In 2015, China’s middle class accounted for 57 percent of the economy, and it should amount to as much as 75 percent by 2030 according to The Economist. Because Chinese consumers are more connected and knowledgeable, and e-commerce in China has been tied to promotions, it would also be natural to believe that affordable luxury would do well with Chinese consumers as well.

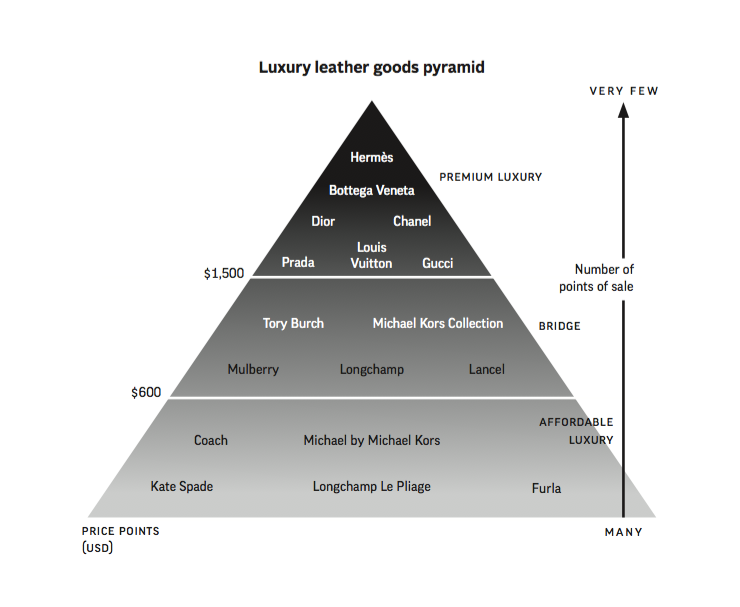

Separately, if looking at the leather goods pyramid of brands, space seems to be available for consumers to logically trade up, with affordable luxury brands building a bridge to aspirational luxury. Many brands stand at the bottom and at the top, leaving a relatively untapped market in between. This is what is often referred to as “white space.” Few affordable luxury brands, however, have been able to penetrate this white space. Coach developed a 1941 collection a few years back, and Longchamp looked to move away from its entry-price-point, best-selling foldable bag (known as Le Pliage) by developing higher-end leather-based products.

All of these factors together should, in theory, create a profitable opportunity for brands to be successful here. The reality has been somewhat different — why?

Reasons for underperformance#

First#

, it is a classic case of buy less, buy better. When consumers decide to spend money on a handbag, they prefer to allocate more money to a premium product. The phenomenon is not limited to bags, of course. Compounding the problem is that traditional luxury players have invested in the white space between affordable and aspirational luxury. Indeed, Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, and smaller European luxury brands driven by streetwear (e.g., Balenciaga), have revamped their access price points, which is resonating well with consumers, and hence, capping the growth of affordable luxury competitors.

Second#

, not being truly global could be an issue. When the world reopens, consumers will again study abroad, vacation internationally, and consume media from all over the globe. Given this, they want to buy brands that are as cosmopolitan as they are, or as they aspire to be. Brands that are not recognized globally do not carry the same status and desirability. This can affect demand, particularly for those that are heavily exposed to one particular region — for example Coach and Michael Kors, which have a majority of their sales in the US.

Third#

, brand equity itself could be affected by the ubiquity of brands or by a strong outlet presence that makes it difficult for the brands to gain prestige. When brands are associated in consumers’ minds with outlets and promotions, they begin to feel accessible and cheap and lose their brand equity. Walking the line between visibility and exclusivity can be difficult. Be too exclusive, and you run the risk of leaving money on the table and alienating potential customers. Be too visible, and your higher-end consumers, who are willing to pay more for your product, will look for more exclusive brands. In luxury, ubiquity doesn’t get you anything; the illusions of scarcity and exclusivity do.

Lastly#

, given the issue of lower brand equity, newly developed secondhand concepts in luxury are eroding the value proposition of affordable luxury brands. You can visit a luxury secondhand store and buy a secondhand Burberry, Prada, or Celine bag at the price of a new affordable brand bag. That is an attractive proposition, especially as you will value the creativity of the premium European brands more. In a visit to an affordable luxury brand flagship recently, I walked the floor with a sales associate who was telling me “this is our take on the so-and-so Prada bag, this is our version of the Vuitton whatever carry-on” and so forth to the point where I had to ask her what was developed from scratch for the brand itself. Not much. Sure, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but imitation doesn’t buy loyalty. If you can get the original secondhand at the same price, why bother purchasing the affordable luxury equivalent?

Handbags are a very tough market for affordable luxury brands, given the status-seeking of the buyer, the crowded nature of the sector, and the reality that consumers will want to trade up to stronger brand equity propositions. Jewelry and ready-to-wear affordable brands, in my view, have much more potential for growth in China and beyond.

Erwan Rambourg has been a top-ranked analyst covering the luxury and sporting goods sectors. After eight years as a Marketing Manager in the luxury industry, notably for LVMH and Richemont, he is now a Managing Director and Global Head of Consumer & Retail equity research. He is also the author of Future Luxe: What’s Ahead for the Business of Luxury (2020) and The Bling Dynasty: Why the Reign of Chinese Luxury Shoppers Has Only Just Begun (2014).