“I’ve always believed that there are so many different standards for beauty, and I’m tired of being told that you are not skinny enough, your color is not light enough, and your eyes, your lips… and everything.” —Naomi Wang (王菊), Chinese singer, in English, in a Fenty commercial.

Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty has been making great strides in China since entering the market in August 2019. During last year’s Singles’ Day, only two months after launching on Alibaba’s Tmall, Fenty was the number one ranked new beauty store on the platform, selling 82,000 items for an estimated 21.7 million yuan (3.15 million) in sales. The brand's decision to have Wang represent Fenty Face — Fenty’s makeup method for all Fenty products — has also won praise from Chinese netizens and media.

Fenty’s success in China was not necessarily guaranteed. In the US, however, Fenty was able to leverage not only its founder’s superstar status, but also its call for inclusivity for all women of color, epitomized by the 40 shades of Fenty foundations. But in China, with 91.5% of the population Han Chinese, who also happen to speak Mandarin as their mother tongue, the inclusion of the 113 million people that make up China’s 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities has been less successful socially, not to mention in the beauty market. But this is a huge, untapped segment. To put things into perspective, the size of China’s ethnic minorities is almost twice the entire population of the UK.

In China, Fenty's marketing efforts have been focused on being “trendy and cool” with some “inclusivity” element mixed in, according to market experts and sources close to the matter. It wants people to accept that there are various standards of beauty instead of simply an idealized fair skin, one of the sources said. Wang's appointment as an ambassador aligns with this mission.

Other than Fenty’s foray into China, with its own interpretation of “inclusive” for the market, what “inclusive” actually means in this seemingly homogenous nation is yet to be determined. With brands like Fenty starting the conversation around “inclusivity,” is China ready for more? Are there other opportunities for brands? Jing Daily examines what defines the term, and whether China is truly ready for inclusive beauty.

Traditional beauty standards remain hard to crack#

China’s traditional beauty standard is encapsulated by slang such as “a white complexion can hide hundreds of faults” (一白遮百丑). The country’s racial hierarchy, which was articulated by Chinese Scholar-Translator Yan Fu in the late 19th Century as non-whites being inferior, is still prevalent. While being combined with stereotypical class perceptions — Chinese people with dark skin tones are considered farmers who need to spend less time under the sun — it ultimately gave birth to the multi-dollar skin whitening market.

As the second biggest beauty market in the world, according to J.P. Morgan, China has been a big driver of revenue for international cosmetic brands and the skin lightening market shows no sign of shrinkage. In 2016, the skin lightening market in China was 1.66 billion but is projected to increase to 3 billion by 2025, according to Grand View Research’s report published last August.

Analysis on China’s new super app, Little Red Book, tells all. When you search “whitening” on the app, you can get over 950,000 posts on recommendations of natural whitening food, medical whitening injection shots, and for the most part, skin whitening makeup. On the same app, however, only a small fraction of influencers are sharing how they tan or draw freckles. There are about 320,000 posts under the keyword “tanning” and 10,000 posts under “freckles makeup,” which are sizable but pale in comparison to whitening, and reflects the market demand driven by the traditional beauty standards.

And brands that dared to challenge China’s mass market beauty standards have struggled. Last February, for example, the freckles on the face of 25-year-old model Li Jingwen in Zara’s digital ad garnered less than a million views — but also controversy, with many comments from Chinese netizens stating that Zara has “uglified” Chinese beauty standards, because a typical Chinese girl doesn’t have freckles.

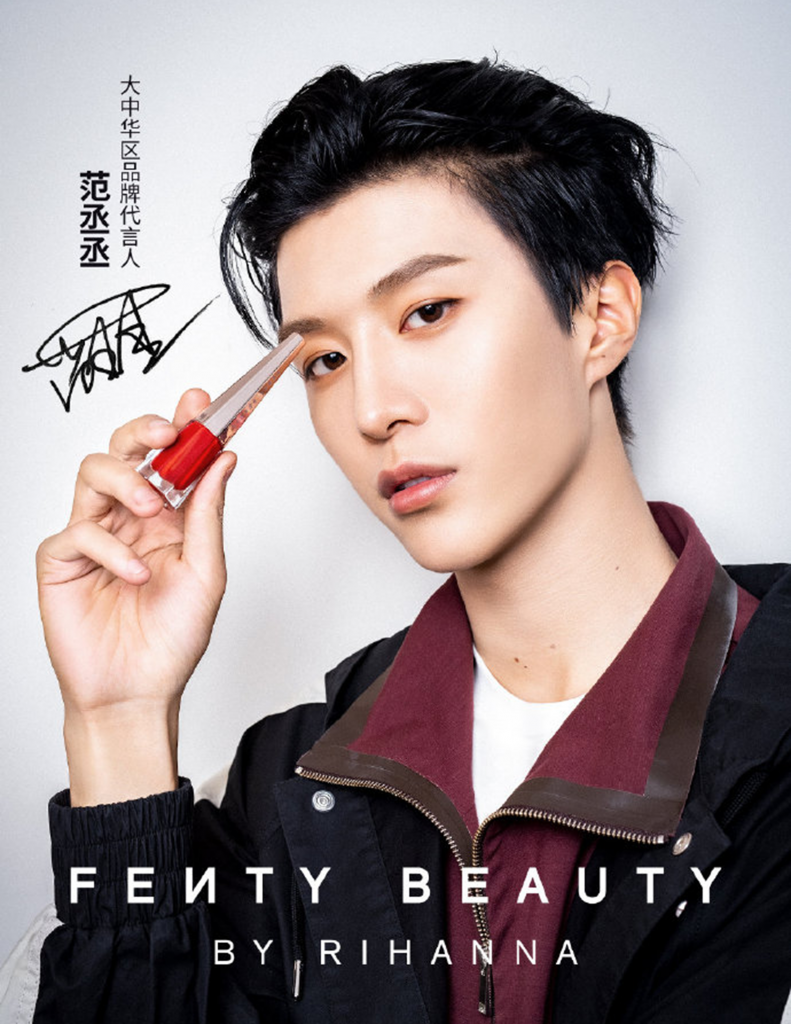

To date in China, freckles and tanning are an acquired taste, which might also explain why Naomi Wang only represents Fenty Face, instead of standing shoulder to shoulder with Chinese singer and rapper Fan Chengcheng (范丞丞) and Singaporean actress Eleanor Lee (李凯馨) as its brand ambassadors. “Wang’s case doesn’t happen often because China’s understanding of ‘beauty’ is still relatively homogenous,” Du said. For brands, whether or not to challenge the beauty aesthetics of a massive market is a balancing act, one that presents both risks and opportunities.

“Inclusivity” in China remains undefined, which presents an opportunity for brands#

While a long roster of names including Fenty, Coty, Mented Cosmetics, and NYX Professional Makeup come under the inclusive makeup umbrella, and are made to suit different ages, genders and ethnicities, the definition of “inclusive” in China remains in limbo, which makes it difficult for brands to target their ideal audience.

Even research experts struggle to put their finger on it. Jing Daily reached out to international research firms, Mintel and Kantar, which both said they don’t have sufficient data to comment on whether “inclusive” beauty is an actual trend. But based on Jing Daily’s analysis, there are signs cropping up that challenge China’s singular standard of beauty. “The local interpretation of ‘inclusive’ might be diverse self-expressions,” said Wenqi Du, the former planning director of digital agency Isobar’s Shanghai office.

Sporting a tan represents one expression. However, standing amongst other contestants who fit traditional aesthetics, Wang, now one of Fenty’s stars, was called “stout” and “dark-skinned” by an army of China’snetizens when she first appeared on the Chinese talent show “Produce 101” in 2018.

However, when Fenty revealed last year that it was hiring Wang to represent Fenty Face, reactions on social media were washed over by praise. “This is such a fitting endorsement!” read one comment while, “There should be more females in China like Naomi,” read another below Fenty’s official announcement on Weibo. In this case, the brand itself shifted the public discourse around inclusivity, highlighting the power of brands to drive and change public opinion.

With Fenty’s endorsement, a symbiotic relationship has emerged and Wang’s message of diversity has also been amplified. However, while this messaging resonates with China’s younger generations, older generations remain harder to crack.

Despite an unclear definition of inclusivity, young consumers are embracing the shift in tone about beauty. “Young people’s perception about dark skin tones are changing, some people see it as a way to show their personality,” said Ivy Fan, an ethnographer at Shanghai-based market research agency Youthology, which tracks China’s Gen-Z and Millennial consumption trends for clients including Procter & Gamble and L’Oréal.

As shifts of social perceptions in China begin to take place, opportunities for winning the younger market segment are up for grabs. So far, not many brands have publicly supported consumers’ self-expression but those who have may have a leg up in the race.

While women are behind, men are ahead#

While beauty standards for women in China are well defined, for men, they are wide open.

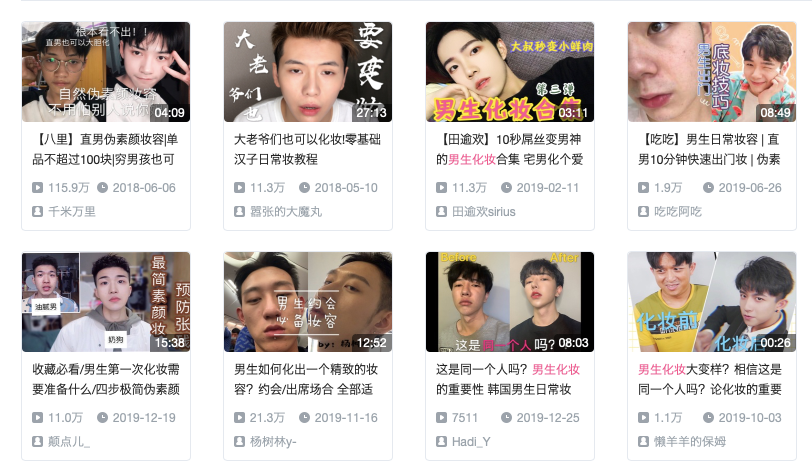

Beauty and makeup in China are no longer exclusive to females. To Nathan Xiang, the rise of young male wearing make up has a lot to do with the gay community and bloggers on social media. “I became interested in make-up at 19 when I was an English major at Wuhan University,” the 25-year-old translator said. “I first came across beauty bloggers on Weibo and I was the first guy in my year to wear makeup.”

Xiang has been open about his sexuality to friends since middle school, he said. Having grown up in Changsha, Hunan Province, he studied in Wuhan and Beijing before moving to New York City last year. He considers male makeup lines, like BOY DE CHANEL, a “marketing hoax,” adding that he only buys female drugstore brands in both China and the US.

The importance of the male market cannot be underestimated, particularly due to the rise of the younger generation of men, according to Kantar’s latest Asian beauty trends report published last November. Kantar emphasizes that male skincare offers strong sales potential, but also that the market for male makeup is also wide open.

“China now has a new generation of idols who are very fashionable and know how to preen themselves, like the boy band TFBoys,” explained Fan. “Regardless of their sexual identity, Chinese consumers’ gender expression has become more fluid.”

In China, Fenty’s marketing message has a long way to go before addressing gender and sexuality, although Rihanna has made it clear at the brand’s inception that she wouldn’t use trans models as a "convenient marketing tool.” The Chinese team announced Fan Chengcheng to represent the brand last September. But that is largely seen as a move to capitalize on his female fan following, just like Dior did with Karry Wang, a member of TFBoys.

So far, only a few homegrown brands with price tags parallel to those of American drugstores have included males in their marketing and products. HEDONE, a digital-native brand that aims to “represent Chinese youth’s self identity,” has been featuring male models since its seven-color lip gloss series: “Seven Deadly Sins”. Among which, a glittery dark purple lip gloss, named “Closet,” was worn by a male model in its online commercials and campaign posters. It costs 125 yuan (18) a pop.

There is also male beauty vlogger Benny Dong (董子初)’s personal brand Croxx. Dong, who’s openly gay and made his name on video platform Bilibili, first launched Croxx on Tmall at the end of 2018. The brand’s first online commercial starred the influencer himself and other beauty vloggers from the LGBT community. A 16-color eye shadow palette from Croxx currently sells for 259 yuan (37) online.

The sprouting signs of men's makeup highlights the fragmented nature of what “inclusivity” means in today’s China. While it hasn’t made it into the mainstream conversation, social and market reaction to Fenty and a few homegrown brands prove that there are more opportunities to be had.

Although China’s mass market might still prefer pale and flawless skin to tanning and freckles, changes are taking place steadily and have spoken to a niche audience. Brands shouldn’t wait for the majority of consumers to change their views before taking action.

A conversation about inclusive beauty takes both the market and brands to happen, and given that inclusivity and diversity align with young consumers’ needs to express themselves, brands should take the initiative before it’s too late.

At the same time, brands should also watch out for signals on social platforms and adjust their marketing language and products accordingly, before fast-moving newcomers with less to lose steal the show. “Changes in China take place at lightning speed,” Fan, the ethnographer said. “Brands need to be agile and react fast.”