From monarchs to aristocrats both ancient and modern, Persian carpets have long been favored by elites across the world. With a history dating back to at least 500 B.C., their distinctive aesthetic remains a home decor staple not only in their home region, but for middle-class and affluent homeowners across the United States and Europe.

But one market where Persian carpets are not as well-known is China, where interest in interior design is still developing. Beijing-based Persian carpet gallery Zamani Collection, which stocks pieces ranging in age from brand new to 150 years, has been working to change that with a host of pop-ups and cultural activities across the city aimed at exposing Chinese consumers to one of the world's most famous textiles.

Zamani Collection’s founder Matin Zaman has seen a growing Chinese interest in interior design since he moved to Beijing from Iran and set up shop in 2010. His encyclopedic knowledge of Persian carpets extends from tribal and nomadic weaving to fine palace designs, and stems from his family’s two-century history working in the Persian carpet business in the city of Tabriz, one of Iran’s oldest carpet-weaving centers.

With carpets mostly in the range of 2,000 to 20,000 RMB (around US$300 to $3,000), Zamani Collection offers a combination of antique rugs, tribal pieces, and contemporary creations either collected by Zaman’s family or produced in their workshop—including a project of repurposing and combining fragments of older nomad rugs to create modern, unique designs. Chinese consumers are taking notice, as director Zhang Yimou recently became the owner of a fine antique carpet collected by Zaman’s grandfather. As interest in Persian carpets grows, Zamani Collection will open a gallery in Beijing’s Caochangdi art district this summer.

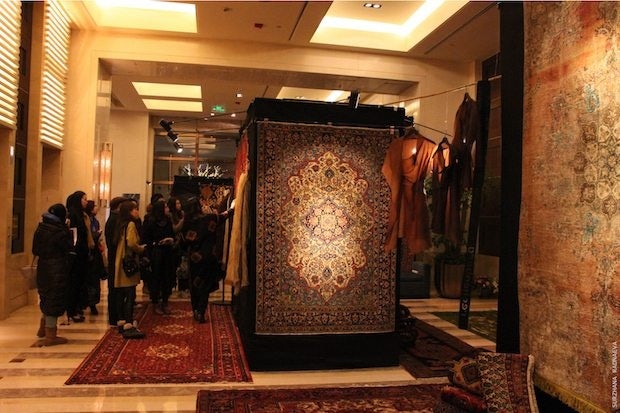

To learn more about the Persian carpet business in Beijing, we caught up with Zaman at Zamani Collection’s recent pop-up collaboration with fashion label Rechenberg at Four Seasons Hotel in Beijing. In the interview below, he shares his thoughts on China's growing interest in interior design, the logistical challenges of importing to Beijing, why Persian carpets are a "national art," and more.

What is the concept behind this exhibition?#

I think we came up with this idea of doing constant exhibitions on the road when we saw that this product is actually very unknown to Chinese. Of course, the Persian rug is famous, but they have have a kind of mysterious image of it in China. They think it’s something that doesn’t exist; it’s only in the stories.

We have to go out there and educate people on what we have here. We are constantly on the road doing exhibitions and pop-ups to get our pieces exposed as much as we can. And we find it highly effective, rather than sitting in a gallery or having a shop—which is an extremely commercial approach—when this is not really a commercial product. This is our national art, basically. You need to give the people a lot of information; you cannot expect people to just drop 200K for a carpet without knowing how it’s made or why it costs so much.

What made you decide to set up this business in Beijing, specifically?#

Actually, it was out of curiosity, because it was our family business for at least two centuries. It works very well everywhere in the world—in the States, in Europe, in Australia—everywhere. China is actually one of the top markets, and there were so many families like us trying to get into it for years, but it just somehow didn't work. I think it was a bit unknown to people, so I decided that I’m going to challenge myself and see how it works.

I think it’s a good time for it now. I think people are getting more into decorating their houses; it’s a new thing. You can also see German brands for the kitchen are moving in and promoting their products.

Why do you think Chinese consumers are getting more interested in home decor now?#

I think because home ownership is actually getting settled. According to what I researched, up to even the 70s, there was not really private ownership of the house. The private property ownership was open in the early 1980s. Now, people are investing in property; they want to have a nice house, maybe increase the value or maybe they’re getting more into the Western lifestyle.

And of course, the most important thing I noticed with the increased mindset is that they’re traveling more. I see so many of my Chinese customers say things like, “We went to London; there were amazing rug stores in the most expensive streets.” It’s very attractive for them when they see an art dealer or a carpet dealer that opens up next to Louis Vuitton; they actually sell something valuable. I think traveling is really increasing the demand for interior in China because they see a lot of hotels; they see a lot of nice spaces—restaurants, cafes. And also those villas that they go to in Spain and Italy—they’re all decorated mostly with rugs.

What types of designs are the most popular with Chinese clients?#

That is very difficult to say. Some people are very into antiques in China in general. I think antique rugs are one of the most popular things in the world. There are so many in the States, especially—we have so many collectors in Europe, it’s extremely in demand to collect.

But what I’ve found out so far, I think in general, people don't like the rugs that are used in China. People like brand new things. Therefore, in our exhibition we’ve been more successful with the modern pieces.

Have you seen any interest in rugs as a collectible item?#

There is, because actually, China itself has quite a few good rugs. They’re not really produced anymore. Xinjiang used to have good rugs, and there was a rug known as “Peking rug,” or “Beijing rug,” which stopped during the 1920s. The colors come from the Chinese porcelain—beige and white and lots of blue, with traditional Chinese motifs on them. There are Ningxia and Gansu rugs, and also Tibetan rugs, of course.

They had quite good rugs themselves, so I think Chinese collectors are mostly into their own rugs. They are not going that far yet to collect Persian antique rugs. But again, traveling is a big factor. If they stay in the States or something for a long time, especially in Germany, I think they get influenced, and those are the ones that appreciate Persian rugs.

What is the process like for finding and selecting the carpets?#

Actually, this is a very small thing. Some of the most highly demanded carpets, like Heriz, come from a village that at the moment has only 7,000 people. The real thing is actually really rare to find. But back in the day, when my grandfather used to do this, he’d basically be going “treasure hunting.” They used to go on the carpet-hunting trips; one by one, they’d visit all the villages and see what local people had for sale or what they were weaving.

Originally, this was art that people would do for themselves. With so many of the tribal pieces I have, it’s basically to decorate their tents; it’s not really for sale. It’s actually extra income for the family sometimes, because they do farming in the summer or spring, and in the winter, they weave rugs. Sometimes, in the spring, they bring it to the bigger cities and offer it to the merchants to sell.

It’s really rooted in our culture; families know each other. It’s very traditional—it’s not really a commercial industrial activity. It’s really something traded between the families; and often they even exchanged land and cattle back in the day.

What are your personal favorite styles that you sell?#

If you categorize carpets, you can categorize them in two types, in general. We call them city carpets and village carpets.

City carpets usually came from the aristocratic families—when the king or someone had a designer, and they used to order it for the mansions and the properties to be weaved. So there was a designer working for the palace, for the king, designing these pieces on the paper, and handing them to the weaver.

But village, or tribal carpets are an entirely different story. They have the family motifs and the entire process is decided and done by one person—improvised, there’s no design. The dye is done by whatever they can get their hands on—pomegranate, saffron, whatever they have.

But city carpets, which come from a royal background, are different. They outsource to get exactly what they want. And it’s usually extremely fine; it’s much, much more expensive. It’s perfectly symmetric. It’s really about details.

Village carpets are more individual. Sometimes you get strange pieces—and those are highly collectible. Personally, I think there’s more aesthetic to tribal and village carpets. I like the feeling more and I think there’s more individuality in them. Especially in recent years, the city carpets have become really commercial. They go and research market demands and then they weave according to that, but with village carpets, they don’t really care about what sells. They do what they want to do. That’s why it’s like pure art.

We have hundreds of thousands of tribes, and each one does their own. It’s really hard to say which one is your favorite. It’s extremely individual. It’s the same as fine art. You cannot say who is your most favorite painter.

Are there any logistical challenges for importing into China?#

It’s very challenging. The challenge is basically that each rug is extremely individual; each tribe weaves them differently, so you cannot really categorize this product. None of them have anything in common with each other—weight-wise, size-wise, and the quality of the wool is different; the age is different. The challenge is that customs has a tough time estimating the value of these. I think my prices are really fair, but sometimes they think because this piece is old, I’m going to sell it for 1 million dollars or something.

Basically, because it’s unknown in China, sometimes it’s very challenging to deal with customs—they don't know how to deal with this.

How do you get the word out about the business to Chinese clients?#

We are heavily using WeChat; we try to promote educational articles that we write—technically explain how it’s done, how the natural dye is done. We try to do shows; we usually do speeches and then we usually combine our events with other things—we do wine tastings while talking about rugs and the history. Each of these villages have their own history, and stories, and why they are weaving what they’re weaving—why is that, why this motif and why not the other motif?

What are the factors that decide the prices of the carpets?#

Nowadays, that’s one of our biggest challenges—in China, so many families are so curious about what I’m doing here. Because in China—it’s actually like so many other products—many are producing a lot of carpets using our design, basically weaving our family name in side of it. They’re selling under our name. So many times, I get the question, “Why is this one this price and yours is this price?”

Technically speaking, there are three or four elements that determine the value of a carpet. Of course, there’s a technical side of of—how it’s woven, the way they knotted it, how fine it is, but one of the most important things, especially for people who are looking for an original and genuine thing for collectors, or somebody who wants to have a real piece is basically the people who made it. If I have a Shiraz carpet, it has to come from Shiraz. You cannot have a Shiraz carpet from Guangzhou, or from India, or from Pakistan.

So that’s actually a huge difference, because those people are limited—how many weavers do we have in Shiraz? A few thousand, maybe. An average 2x3 piece of carpet takes them maybe more than a year to weave. So the production is very limited. That’s why the price is high.

Or you can get a copied version like in some workshop inside of China—they take one of our carpets and make 1,000 of it, using the chemical dyes or cheap wool, whatever they can, just to get the same look. What people don’t know is that’s much more than that goes into it.

That’s actually a big challenge for us—to educate people on why they are paying this much. What’s the difference between hand-spun wool and machine-spun wool, or what’s the difference between chemical dye and natural dye, or what’s the difference between doing a double knot and single knot? There’s so much technique inside of it; it’s a big subject to talk about. But in general, if you’re buying a carpet, it’s exactly like buying artwork; if you’re not buying from the people who are making it, it’s just like a Picasso poster or something. We have an expression saying, “you’re not really buying a carpet, you’re buying a picture of it.”

This interview was edited and condensed.