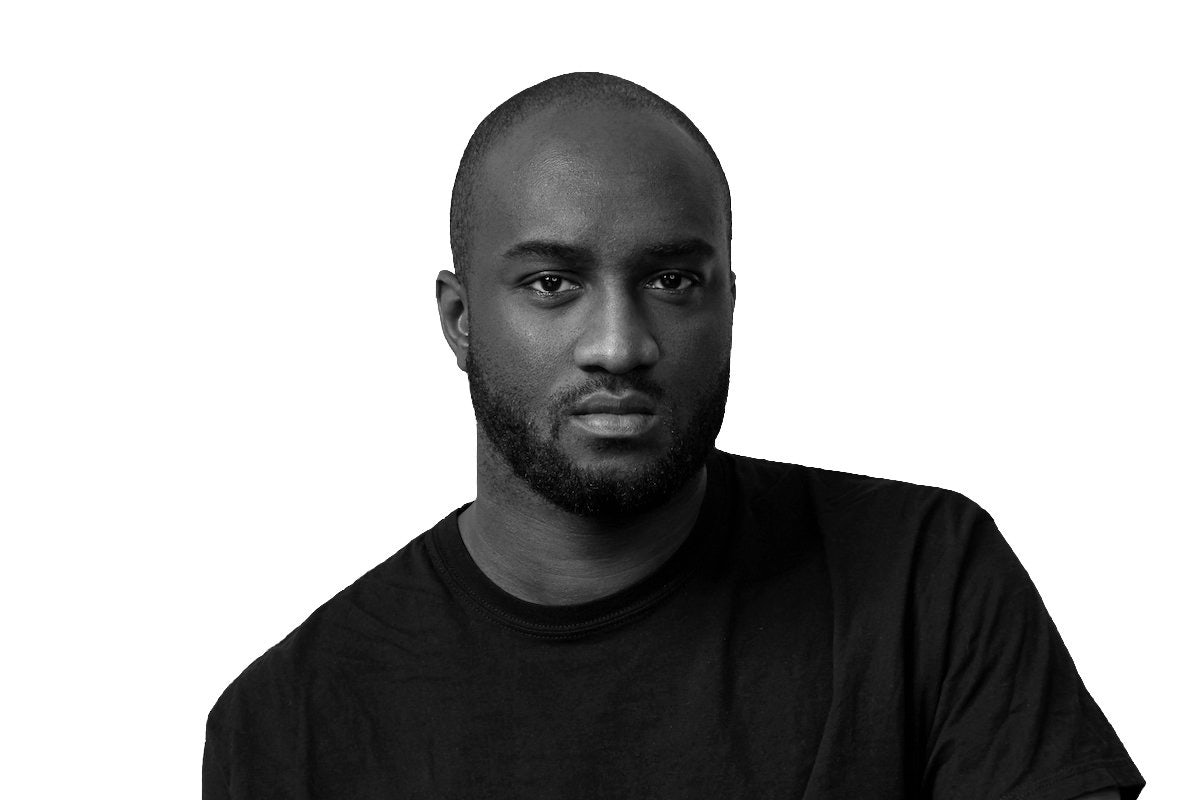

Modern Collectibles is analyzing the Virgil Abloh's impact on fashion in partnership with Sotheby’s. Visit Sotheby’s to purchase pieces made by the late designer for Louis Vuitton.

“Anything could be mixed and matched – or mashed up, as is said today – and anything was fair game for inspiration,” noted musician David Byrne of postmodernism’s heyday in a V&A exhibition on the movement. From music, to architecture, to literature, and sculpture, postmodernism has spread to almost all art forms and design disciplines. That includes, of course, fashion, with designers playing with postmodernism’s pastiche and irony going back to the '70s and '80s.

But few in the fashion space propelled the movement’s ideas to a mainstream platform the way Virgil Abloh did. The late designer’s prolific output of collaborative, multidisciplinary products featuring his famed quotation marks and “3 percent rule” made postmodern ideas in fashion not only widespread, but relevant in a way traditional and emerging audiences couldn’t help but find infectious.

Abloh was not a traditional fashion designer, not merely in the sense that his formal training was in architecture, but also in the way he used design holistically. Fashion design in Abloh’s universe was not just about making clothes, but crafting the space in which they exist, whether that was creating an installation with artist Jenny Holzer along with a collaborative T-shirt for Pitti Uomo, having Playboi Carti model his see-through holographic Louis Vuitton keepall down the runway, or sending a pair of the Air Jordans from his “The Ten” collection with Nike to Roger Federer prior to their official release.

“He's approaching fashion, the glamour aspect that we understand coming from our end of the spectrum, from a place of functionality, a place of democratization, a place of strategy. And that’s something that fancies a lot of his audience, and certainly is what set him apart from a lot of his peers,” says Darnell-Jamal Lisby, fashion historian and assistant curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Placing his work in a pop culture context accessible to a young audience was as much a part of the design as the pieces themselves, whether that was a luxury bag or a popular pair of sneakers, as boundaries between high and mass fashion only existed to be played with.

“That entrance of street culture, urban culture, really kind of solidified itself around the time into luxury fashion. Virgil was sort of swept up in that transition, even though that transition had begun decades before with the likes of Willi Smith and Dapper Dan back in the 1970s and ’80s,” Lisby adds.

Abloh was famed for his “3 percent rule,” by which he believed that you only needed to change an object by 3 percent to create something new. “A creative only has to add a 3 percent tweak to a pre-existing concept in order to generate a cultural contribution deemed innovative – for instance, a DJ only needs to make small edits to innovate a song. Likewise, a designer would only need to add holes to an iconic handbag to leave his mark,” he stated. Some critics lambasted his work as mere “copying,” but in doing so missed the intentionality behind his references.

“Something special about Virgil’s design approach is that he was incredibly efficient in the way he altered and hacked into items from other brands. He obviously had his famous 3 percent rule, but what people don’t think about enough with that is that changing something by 3 percent can do a lot to an object,” says Thom Bettridge, Head of Creative and Content for SSENSE, citing Abloh’s clear Rimowa suitcases or use of handwritten lettering on a mass-produced Nike shoe. The final design could be simple because the idea was the design, whether it was a sneaker or a car or a water bottle. “The end result was simply the vessel for the idea,” Bettridge adds.

"I think Virgil’s brand of irony resonated with people because it wasn’t cynical. It came from a place of identifying very real contradictions."

Perhaps Abloh’s most recognizable signature was his use of quotation marks on everything from knee-high boots to collaborative bags with Ikea, with his choice of words often suggesting that the actual products were merely symbols for a larger idea. Such a satirical stance can often create a cold distance with a viewer, but Abloh’s work instead often inspired a strong emotional connection with his audience.

“I think Virgil’s brand of irony resonated with people because it wasn’t cynical. It came from a place of identifying very real contradictions,” notes Bettridge. Take his “a formality” tie, for example, which put into clear words the breakdown of formal wear that his followers were already engaging with.

Abloh applied his philosophy to all kinds of objects, from album covers to cars. But fashion remained an especially useful conduit to explore his ideas due to the medium’s timeliness, notes Lisby. When viewers see Abloh’s work in museums from years to come, whether it’s his dress created for Beyoncé to wear on tour or his sneaker collaborations, they will also immediately see those works as a product of a time and place.

“If I, for instance, took an 18th century dress from France, I can tell you everything about what's going on at that time, from a textile fabrication place, to a fashion style point, to a cultural political place,” says Lisby. “Because fashion represents that, and is an intersection and really also a language that communicates beyond our cultural boundaries and generational boundaries. It's something that resonates with all of us, that Virgil then took on for himself to use in his own way, and use it as a unifying tool.”

Even while Abloh’s work acts as a time capsule, it will also carry on in how he opened up the idea of what a fashion designer can be. Not only in designers working today, like journalist and stylist Ib Kamara as Abloh’s direct successor at Off-White, or Demna’s work at Balenciaga in challenging our conception of haute couture, but in future generations yet to enter the profession. “[Abloh] left a trail of breadcrumbs behind him, and it allowed young people to not think of fashion as a purely foreign thing, but rather as something that was possible for them to participate in,” says Bettridge.