It was 1997 when Shanghai-based partners Shouzeng Ye and Shawna Tao decided to start an ethical fashion brand. The couple had studied design at one of China's leading design schools, Donghua University, and upon graduating felt the market didn’t offer what they had in mind for the modern Chinese consumer. The country’s rapid urbanization was creating a need for professional clothes but the couple couldn’t see anyone offering quality pieces in natural fabrics.

From this, Icicle was born, with “the mission to use fashion to build a connection between humanity and nature,” explains Tao from her home in Paris. “It is a basis of Taoist philosophy to recognize that we are not equal with nature. And back then, as it is today, respect for nature was at the heart of our thinking. We constantly ask ourselves if we are following the rule of nature or not.”

It was an enlightened approach 25 years ago, long before the world woke up to the horrors the apparel industry was wreaking on the planet and sustainability became a subject on every label’s drop-down menu. It was also entirely counter-intuitive to the approach of the rest of the Chinese fashion sector. Back then, Made in China meant “we can get a lot of it, quite cheaply, with synthetics.” How things change.

Icicle was ahead of its time, but careful nurturing allowed it to flourish. As the label grew, its sustainable practices extended beyond natural fabrics and classic designs to a more emotional approach. “One of our pillars is, ‘cherish what is given to us,’ and another is ‘caring.’ We care for our employees but also our heritage by supporting traditional Chinese craftsmen to develop products, such as Suzhou embroidery,” adds Tao.

Today, Icicle is one of China’s best-known luxury labels with over 250 stores on the mainland and three in Paris. The values it has stood for over the last quarter century seem, well, to finally be in fashion.

There is much for other groups to learn from in their success story. While western environmentalists like to batter consumer audiences over the head with material science, PhDs, and tales of impending climatic doom, companies find these messages mostly fall on deaf ears when it comes to Chinese shoppers. As Icicle’s success shows, the domestic audience responds to a more nuanced approach.

“Sustainability in itself is not a core criterion driving Chinese consumers,” notes Anais Bournonville of Shanghai-based Gentleman’s Marketing Agency. “A few years ago, it was not engaging and even repellent.” However, the industry is evolving, particularly for younger audiences. “The evolution mainly concerns Gen Z who have traveled or studied abroad, and have a better understanding of green development. The advocacy of this young generation, combined with the latest government policies to become carbon neutral by 2030, has changed the market.”

Still, communicating sustainability as part of the reason to purchase requires an understanding of the appetite of the broader audience

.#

Businesses that have gone in with a “sustainability first” or “sustainability only” approach have fallen flat on their faces. The watch brand WeWood offers a cautionary example. “Their slogan was “purchase a watch, plant a tree,” which was effective in the west but did not work amongst Chinese consumers,” states Bournonville. “The main reason was a lack of understanding for the local customers in terms of value creation, emotions, and worth. The mistake international brands make is to focus only on the environmental pillar while forgetting about the social and economic ones.”

The watch firm Jacques Lemans, on the other hand, got it right. For their 2021 Eco Power Solar collection, while they chose to highlight vegan leather and solar movement to their western audience. “In China, they focused instead on the preservation of the next generation,” observes Bourneville, highlighting “a social commitment to the local production in Austria, where it is made.” Personal health is also an important touchstone for the domestic audience: a 2021 Accenture report found that Chinese consumers care a lot more about their physical wellbeing and have a greater desire to pursue a healthy lifestyle. If sustainability can be linked to aspects like these, it’s a winning message.

If you can get the messaging right, a younger generation of consumers — riding the economic boom and educated about the environmental pollution costs of manufacturing — will respond accordingly. Take the “plastic-free” policy. “Europe always highlights plastic pollution in the oceans as something that affects the marine fauna and flora, contaminates our food, and affects our interactions with the sea. In China, such reasoning will have less impact,” Bournonville comments. Luxury houses need to make it relevant. “The plastic-free policy is more impactful when it highlights the contamination and effects of micro-plastic on our own health.”

After working in Hong Kong and the mainland for 15 years, Christina Dean, founder of the circular fashion NGO Redress, thinks this is the key to sustainability messaging. “The Chinese have got a backbone of industry, meaning they really get the environmental impact of production. This is the beauty of the Chinese consumer — there is a visceral reaction to wanting to see fashion change. Because it's in their water, it's in their soil, it's in their air and it's actually polluting them. Whilst climate is everybody, textile pollution is China,” Dean argues.

Bournonville agrees. “When we talk about the environment, Chinese consumers mainly care about health and family. It is important to investigate local culture and values to understand the predominance of family, the preservation of the next generations, and the importance of health.” In other words, between east and west, it’s a play-off between emotion and advocacy.

When we talk about the environment, Chinese consumers mainly care about health and family.

Chinese audiences will often find overly factual sustainability messaging heavy and oppressive. “Brands need to put more humanity in the motivations of sustainable consumption,” Bournonville continues. “Western consumers have the feeling that they do not do enough, that they should have sustainable consumption in every aspect of their life, while the daily news reminds them of the catastrophe to come.

"In China, consumption is fun and playful. Western brands who communicated these messages missed their target because Chinese consumers consider their communication to be dull and killjoy. Homegrown brands that managed to communicate the right message played on the emotions — if you purchase this sustainable item, you protect your health or protect your family. They always come back to the why: why we protect the environment, why we take a stand on social matters, and why we fight for economic growth.”

Mei Chin is a 28-year-old designer living in Chengdu and a good representative of changing attitudes among the young. “My lifestyle and shopping have always been very low-desire and minimalist, and have become even more so in recent years.” For her, handicrafts, domestic manufacturing, second-hand goods, slow fashion, and “other more emotional information” are what attract her attention. “This is the quickest and most direct way to make people feel that they are contributing to environmental protection, and it has a strong aspect of social media dissemination,” she remarks.

Chin points to Klee Klee as a name she admires, for the way it focuses on sustainable development through the continuation of traditional handicrafts. “It makes young people feel the attraction of slow fashion and lets more people join in with this concept,” she says. Chin’s comments reinforce the results of a survey by data venture Altiant, which revealed that younger shoppers are almost twice as likely to buy sustainable goods than their older counterparts: 41 percent in the 18–41 age bracket, versus 24 percent aged 42–57.

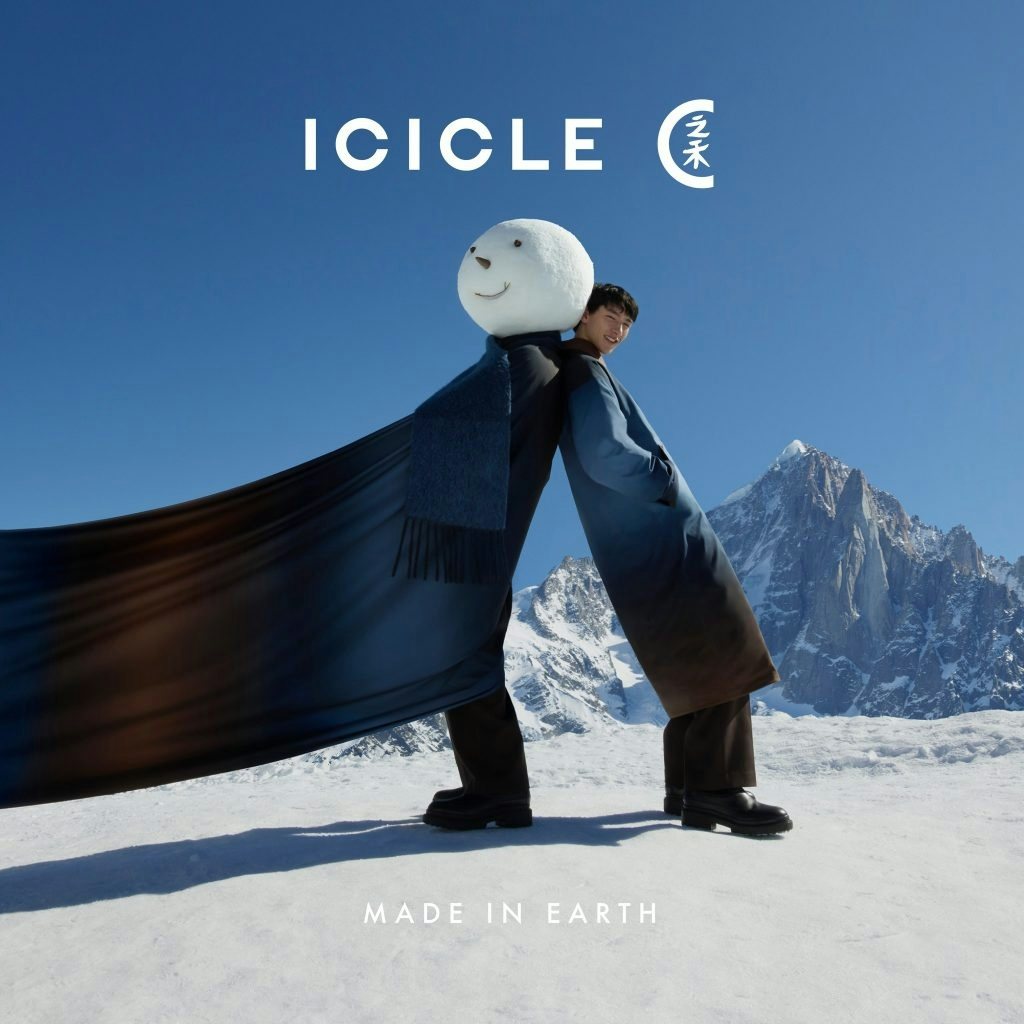

“Icicle’s ‘Made in Earth’ storytelling managed to seduce Chinese consumers,” Bournonville asserts. “By cultivating a company that is ethical and fair, it has reinterpreted what it means to be ‘Made in China.’ This is the main evolution of the market in the last two years, driven by Guochao (国朝) or national pride. Today, young generations do not call it ‘Made in China’ but ‘Designed in China.’ They do not consider themselves the ‘world’s factory’ anymore but as creators who can design fashion brands and drive international trends." Dean concurs that there seems to be a resurgence in craft “in response to luxury’s desire to separate from the mass market. Beautiful artisanal craft and heritage define luxury — and that has a lot of sustainability attributes.”

One establishment that seems to have brought all these messages together is Timberland. “We noticed that an increasing number of young consumers in China pay more attention to the environment,” reports Winnie Ma, President of VF Corporation APAC, Timberland’s parent enterprise. The group recognizes its fashion-savvy customer is likely to be younger and more widely traveled. “They like to pursue an eco-friendly lifestyle, which includes choosing products and brands with natural or sustainably sourced materials and ingredients.” Eco-innovation has long been part of the Timberland design strategy, demonstrated by a long-standing collaboration with the British designer Christopher Raeburn, renowned for his responsible approach and progressive aesthetic.

To bring local meaning to Timberland’s environmental stance, the institution has worked with Dean’s organization Redress for the last three years. Together, they run a competition for global designers to produce green designs. The winner is then tasked with designing a capsule collection themed around Chinese New Year. “Our partnership with Redress is based on the understanding that if we don't cultivate relationships early on in the career of a designer's life, the future of the fashion industry will struggle,” says Ma.

That future depends on labels taking their audiences along with them. “The sustainability thing shouldn’t be finger waggy,” Dean concludes. “‘You mustn’t shop, you mustn't do this, you mustn't do that.’ No one wants to hear that. We have to evoke something beautiful. And you do that through quality, durability, and aspiration. You don't have to scream sustainability to get it into someone's heart and mind. There’s a gentler, more beautiful way of communicating.” If brands can master this, their parent companies, the sector at large — and even the world — all stand to benefit.