This post originally appeared on Content Commerce Insider, our sister publication on branded entertainment.

Last month, when Instagram revealed a recent update to emphasize its Shopping and Reel features, it was met with outrage across Western social media, with the leading beauty influencer James Charles stating that the platform was pushing “features that literally no one is asking for.” Despite Instagram being an #ad money-making machine for brands, Western consumers continue to view social media primarily as a creative outlet rather than a commercial one.

Over in China, however, it’s a very different scene, with social commerce sales surpassing 186 billion in 2019 [eMarketer] — ten times the U.S. total, thanks to the deeper integration of content and commerce and its embrace by consumers. In short, there is one phenomenon taking over e-commerce worldwide, just with two very different stories.

Social media commentator Matt Navarra told CCI that, while Charles may be voicing public opposition to Instagram’s latest moves, he also sells out merchandise by marketing on that very platform. “I don’t think [the West] is opposed to shopping on social media platforms, I think that it’s just a relative novelty because there isn’t a fully fledged shopping platform yet,” said Navarra. “I think there’s more of an uproar of people liking other features and not liking change, having to adapt how they use the platform.”

Western social commerce is currently dominated by advertising, rather than transactions. After all, influencer culture is Instagram’s most dominant force, built upon brand marketing. “People love to gather around an individual that represents something they resonate with or support, or find aspirational or inspirational,” said Navarra, noting how influencers carve out online subcultures molded by aesthetics and common values, which brands then emulate.

Social media has also created new expectations of transparency, personality, and relatability in brand storytelling. The past year has seen certain products going viral on TikTok in 2020 without direct brand involvement (or control), proving the power of social content, from Nathan Apodaca skateboarding while drinking Ocean Spray and Sherwin Williams’s paint mixer to the Le Creuset obsession and Revlon’s 2-in-1 hair dryer review videos.

“Brands are seeing their products succeeding better from viral posts than from advertising movements because TikTok trends bring a sense of personability to a product,” said Pippa Speed, associate at London-based marketing agency Truffle Social. “It adds dimensions to what would originally have been promoted directly from the brand.”

Purchases are predominantly influenced by social media, but the West is yet to pick up the pace of China when it comes to integration of mobile payments. For example, last year Tencent’s WeChat saw mini programs generate transactions valued at more than 115 billion. (eMarketer)

Rui Ma, co-host of Pandaily’s Tech Buzz China podcast, told CCI that WeChat owes its success to influencer culture as well as its simple-to-share structure. “You are either led to the product by your friends, or you purchase directly from a person, i.e. influencer,” said Ma. “The former was helped by the fact that WeChat was such a great product for sharing — especially through unique features such as mini programs — and the latter was just much more normal in China, with endorsements always being a big deal and commission-based shopping guides a common fixture in many Chinese stores.”

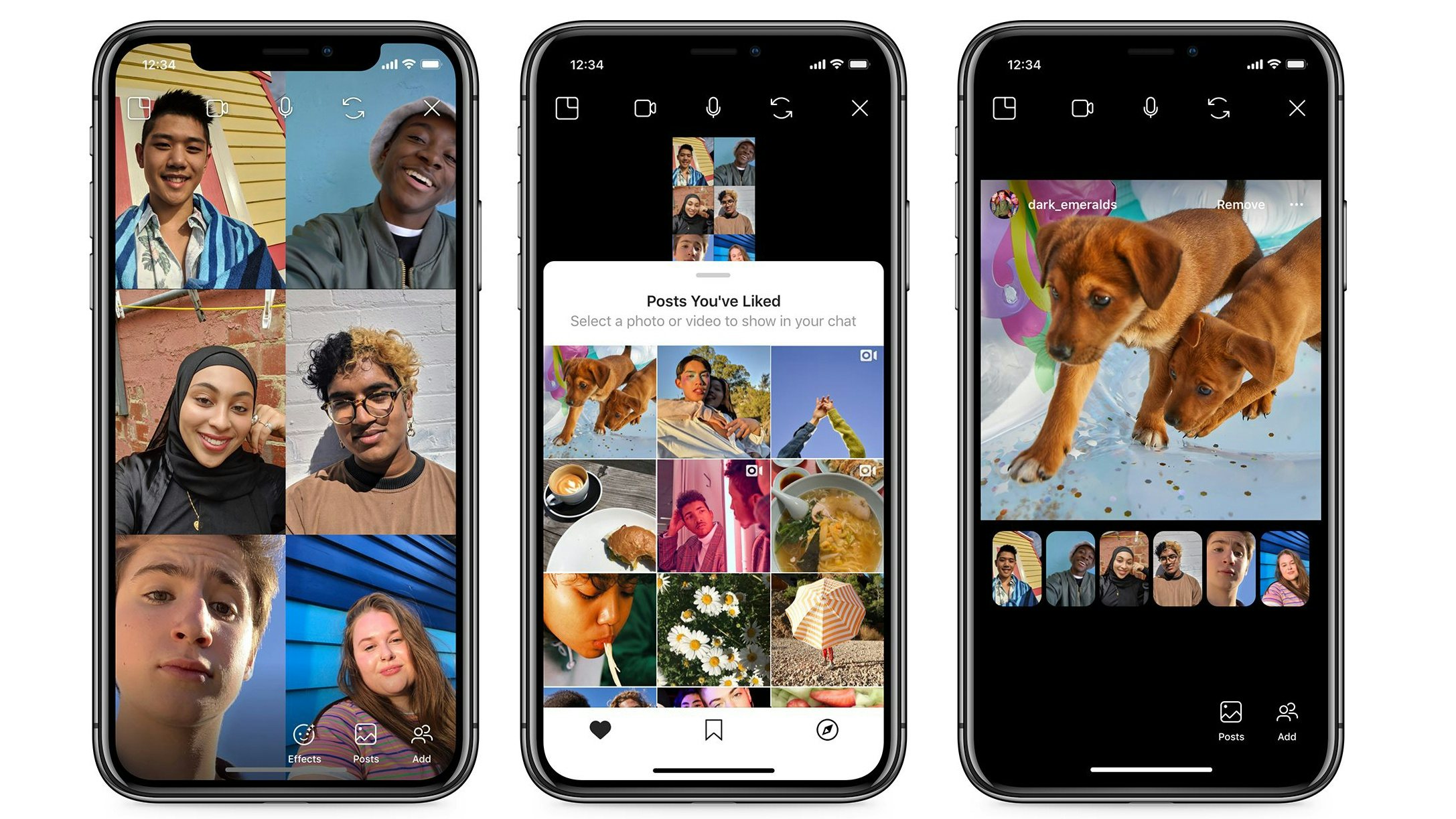

Influencer marketing is the common thread in these two social commerce stories, yet the structures of the most popular apps differ. Instagram is algorithm-driven, whereas China’s leading social commerce app WeChat is not. “[Instagram] is trying to keep people on the platform as long as possible, that is definitely a motivation,” said Navarra. “The difference is in Western countries, apps don’t have the same integration into their daily lives with one specific app to do lots of things.”

WeChat founder Allen Zhang crafted his do-everything app with pure functionality in mind, which is why there are no ads on the open screen and messages do not show read receipts. WeChat thus offers a more relaxing social shopping journey, giving users access to mini program stores, rather than forcing products upon them in the time-sucking, ad-bombarding Instagram mode.

Perhaps WhatsApp’s shift toward in-app e-commerce is the sign that U.S. tech is finally digesting China’s social commerce story. The Facebook-owned messaging service recently introduced catalogs and shopping carts, allowing users to browse and add products from different retailers. However, if WhatsApp were to reach a comparable level as WeChat (which currently hosts some 2.3 million mini programs) Google and Apple would stand to lose out exponentially — the former currently has 2.87 million apps on its store, and Apple has 1.96 million. (LD Investments)

Livestreaming is another element that factors into China’s social commerce success while yet to take off in the West. Even pioneers such as Bytedance, which launched e-commerce on Douyin in 2018, has only just started to roll out shopping features on its global counterpart TikTok.

The coming year is sure to reveal whether the West is following China’s social commerce strategies, or whether it is simply choosing to continue on a different journey.