Director Discusses Current State Of Filmmaking In China, Young Directors, MoMA Retrospective#

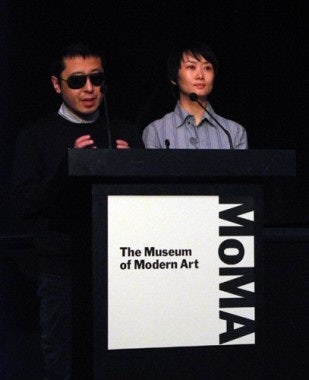

Last week, the Jing Daily team had the opportunity to interview Jia Zhangke (Platform, Still Life, 24 City), one of China's top contemporary filmmakers, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York during its retrospective of Jia's work. (The event continues through March 20.) Conducted in Mandarin, our 30-minute interview covered a range of important topics in the world of Chinese cinema, and shed light on Jia Zhangke's opinions about everything from the current state of the official Chinese film system to the importance of nurturing young talent to the key developments in today's China that inspire him as a filmmaker.

In

Part One#

of our two-part interview, Jia discusses the key developments in film production in China, his personal experiences as a young director in Beijing in the mid-'90s and support of young directors there today, and the difference between being an "underground" director and one who operates within China's state film system. Next Wednesday (March 24), we will post

Part Two#

, in which Jia discusses his film production company, XStream, and some of the upcoming projects he is currently involved in -- both as a director and producer. The Jing Daily team would like to thank Jia Zhangke and Eva Lam of XStream for their time, and express our gratitude to Jytte Jensen and Meg Blackburn of MoMA for organizing the interview.

JD: Can you tell us a little about the current state of film production in China? What changes in particular have you noticed in the last 5-10 years?#

JZK#

: In terms of the industry side, we’re in the midst of the rapid development of the Chinese film industry. Why do I say it’s a period of rapid development? Because in the not-so-distant past, in the 1990s, for a while there a lot of screens simply disappeared, lots of theaters closed down, especially in medium- to small cities. Basically there were no [movie] screens. After 2003, however, development of the movie industry really sped up, particularly in big cities. The number of screens skyrocketed. Last year, I saw a figure that every day 1.7 new screens are opening up [in China]. That’s a pretty big deal. It really is developing quickly.

In terms of output, I’m not sure of the exact numbers, but in 2002 or 2004, the entire Chinese movie industry only pulled in around 1 billion RMB. Last year, it made 6 billion. That’s sixfold growth.

But development in the Chinese film industry has been a bit unbalanced. Up to this point, most movie theatres have been concentrated in China’s large, developed cities – for example, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Chongqing, Wuhan. These huge cities make up the bulk of box office receipts. But actually, most of the 1.3 billion people in China are distributed throughout villages and small towns. So on the one hand, it’s unbalanced, but on the other hand I see it as an opportunity for the Chinese film industry, because if in the future more theaters are built in more remote areas, it’s going to be really powerful. This is from a development perspective.

You also asked about the changes I’ve seen in the past five to ten years. Actually, I think the Chinese film industry is still at an early stage, because so far Chinese films really have had to rely on the state-owned studio system. Particularly in terms of film creation and production, this is still primarily controlled by a few large production companies, like the China Film Group or Shanghai Film Group—they’re all state-owned enterprises. There are lots of private film investors, but their productions still include the state-run organizations at some point down the line, so from this perspective we can say that the industry really isn’t that prosperous, free or independent. Currently, the film industry and the old system aren’t that far apart.

JD: Sixth Generation filmmakers in China such as yourself have had some impressive achievements. How about the next generation? Are they mostly working underground or within the system? How do you feel about their creative style and form -- do you see any interesting aesthetic values at play? If so, are they attributable to factors like technological advancements, greater access to films from abroad, or changes in the Chinese educational system?#

JZK#

: I feel that the younger generation of filmmakers, those who are younger than me, can be split into two different groups. The first is really interested in the film industry. They want to make commercial movies, work within that broad commercial channel, and really cater to the market. Whatever the market wants, that’s what they’ll shoot: comedy, satire – the kinds of films the public is really fond of. That’s good for them, but at the same time these movies are missing a sense of self. They’re just films that pander to the whims of the market.

But this is only one side of the picture. On the other side are young directors who reject the industry outright, reject the market completely. They shoot their films on shoestring budgets and don’t try to reach a broader audience. Actually, I’ve been trying to promote a new concept of filmmaking in China. If you’re that kind of director who’s interested in making commercial films, those films still need some kind of inner spirit and creativity. They still need to say something about society, about people. Quite simply, commercial films still need some sense of quality.

On the other end, independent art still needs an audience. Independent artists have to work hard to help more people understand their films and join in the independent spirit. So I feel that this is a two-sided coin. Both sides are diametrically opposed to one another, but if both can compromise a little, it’ll benefit the whole industry.

Really I just hope these two sides will balance out a little. Those filmmakers who crave commercial validation can still have some originality, and directors who reject the market can at least warm up a little and want more people to see their movies. That’s better than their films just being seen by a couple of people and discussed within a tiny group. In terms of aesthetic differences, I think it’s quite different than when we were studying film, because the new generation of directors live in a really developed age of information. They can share film information and resources effortlessly.

In Beijing, when I was a student, at that time there was a lot of piracy. I used to call [this area selling pirated films] a “street library”—whatever movie you wanted to see, you could [get there]. This is a cultural phenomenon unique to China. Of course we don’t encourage piracy, but it is a reality, and for some of us it’s a valuable resource.

So in terms of this matter, I feel that the new generation of filmmakers will choose to take wildly different directions in their careers. At the same time, one thing I’ve noticed is how important the Internet is to young directors in China. So many of them are using it to show their movies, even shooting films that are basically shot specifically with the intention of putting them online. This is going to be really important for the Chinese film industry, because it’s very important for the industry to integrate itself with new media.

JD: Could you tell us a little about film distribution? How do most people see movies? At the movie theater? Or do they primarily watch DVDs or stream films online?#

JZK#

: Overall, I think most watch movies online. This is particularly true for people who live in smaller cities or in really remote areas. There are two reasons for this: First, if they want to see the newest films, the most convenient way is to watch them online, because where they live they don’t have any movie theaters. For example, the county where I grew up is pretty big. It has a huge population. But it doesn’t even have one movie theater. So if a film comes out and people there hear about it and want to see it, what other option do they have aside from watching online? So I think the Internet is the main conduit, the fastest way for people to in China to see new movies.

Then there’s DVDs. Actually, I think the people who see movies at theaters are far and away the minority.

Art theaters have had huge difficulties over the past several years, because it’s much easier to see movies online. Before, when there was no Internet or before it was this developed – in the era of the DVD – at least you had to go out to buy DVDs. Art films at that time had a huge audience, mostly comprised of university students. They’d go buy a DVD to watch, or sometimes they’d go to the movie theater. But now pretty much everyone just watches films online.

But the problem is that there’s a lot of piracy online. Like for me—I can sell my movies online officially, but the price is pretty low. So it’s kind of a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation. But that’s inseparable from the national condition of China.

To come back to the second reason why most people watch movies online, movie tickets are really expensive in China. For premier films, tickets cost at least 50 RMB (US$7.32) and can go as high as 120 RMB (US$17.58) – that’s almost as expensive as they are in the U.S., or maybe even more. Going to see a movie has become a really expensive activity. So when people decide to go to the theater, they want to get their money’s worth and tend to choose the imported Hollywood blockbuster over anything else.

Generally, the audiences for art films in China have cultivated themselves on DVDs. They tend to think that DVDs or online video is good enough. So I think it’ll take time to change. I’m not pessimistic about it; I just think it’ll take time.

JD: How about your films? Since 2004, you have made films within the official Chinese film system. Do you think it’s gotten easier for audiences at home to see your movies? Where can they see them? Are you satisfied with the way your films are distributed?#

JZK#

: I’m not that satisfied, because the vast majority of my audience just watches them online. Take Still Life, for example. At the time of its release we took a pretty radical approach. We decided to release it at the same time as [Zhang Yimou’s blockbuster] Curse of the Golden Flower. We didn’t think about commercial interests or the business side of things, we just wanted to call people’s attention to the fact that art films or films that are concerned with the true condition of people’s lives in China exist in a really limited space, because people don’t even realize [that] is a problem in our culture.

When we released the film, I felt like the audience was really small. Still Life only took in something like 1 million RMB at the box office. But afterwards, I found out that the actual number of people who saw Still Life was huge. Most of them had watched it online.

Of course, every director hopes that audiences will choose to see their movies when they’re released in theaters. Because, after all, when the director is making the film, they’re doing it with the big screen in mind, not a DVD. Lighting, sound design, scenery and so forth – like in Still Life or Platform, we had lots of long-range shots and wide vistas, all of which were filmed with the silver screen in mind. I think I just need to be patient, and gradually let people get used to the idea of seeing films like mine at the movie theater.

It’s the kind of thing that you have to put a lot of work into. You can’t just give up on it.

JD: And overseas? From this MoMA retrospective, we can see that American audiences are getting more interested in your work. Do you feel that it’s important for western audiences to enjoy your films? Or do you think the most important thing is for Chinese audiences in particular to become more interested?#

JZK#

: I never make distinctions among audiences. When I make a film I don’t even think about whether it’s for the Chinese market or the western market. Because in my experience, I think audiences are all pretty much the same. I don’t distinguish between the different types of audiences because I don’t think there’s any real difference. No matter who they are, American, French, Japanese, Korean, it's all fine with me.

Of course, this isn’t to say that the cultures aren’t different, that the histories aren’t different. Audiences come from different places and have different backgrounds. They all have differences. But when I go to see a foreign film, an American film for example, it’s not like there are major obstacles for me to understand it. Because I feel that people are, essentially, all alike.

Before, I think people always emphasized cultural differences, cultural gaps. But actually I think film is the easiest thing for different cultures to accept. So I never feel like I shoot films for a Chinese audience, and at the same time I don’t shoot them with a foreign audience in mind. Especially as a Chinese director, I think you have to have faith that the films you shoot can shed light on issues that are universal, not totally esoteric. Because if you’re only dealing with specific emotions, it’s going to be hard for many people to understand. Universal emotions are the most important.

Everyone, no matter who they are, has difficulties with issues of life and death. So why do films always rehash these issues? Because if we see a Japanese movie, we can understand how Japanese people cope with these difficulties. Or we can see how Americans deal with these problems, or the Chinese point of view. We can see the different ways that different cultures resolve their problems, the attitude with which they deal with things. But through it all, these problems and the difficulties of being human are all the same.

So as a filmmaker, I never make a distinction among audiences. I never separate audiences.