Porcelain-like skin, a slim figure, and a cutesy personality are essential building blocks for a typical wanghong (a Chinese word for a female mega-celebrity.) Adopted by many countries around the world, this Westernized beauty standard has been a hard habit to break, particularly in China where women have been cast in docile, dutiful roles for centuries.

Many international brands have come to China over the years trying to spread messages of gender-positivity, attempts that often lead to massive brand fails. And indeed, gender stereotypes in China can frustrate the feminist-minded: Single women over 25-years-old are still called “leftover women” in certain parts of the country and relationship entrepreneurs such as Ayawawa have become incredibly popular by teaching Chinese women how to “marry up” (a.k.a. find a rich husband.)

The mainstream media in China promulgates this female ideal of "young, pretty and deferential", but many Chinese women have grown frustrated, bored, or just burnt out with such monotonous depictions. Fortunately, new role models, movements, and female representations have started popping up in advertising, giving the world a fresher look at evolving gender roles in China:

The Wang Ju Phenomenon#

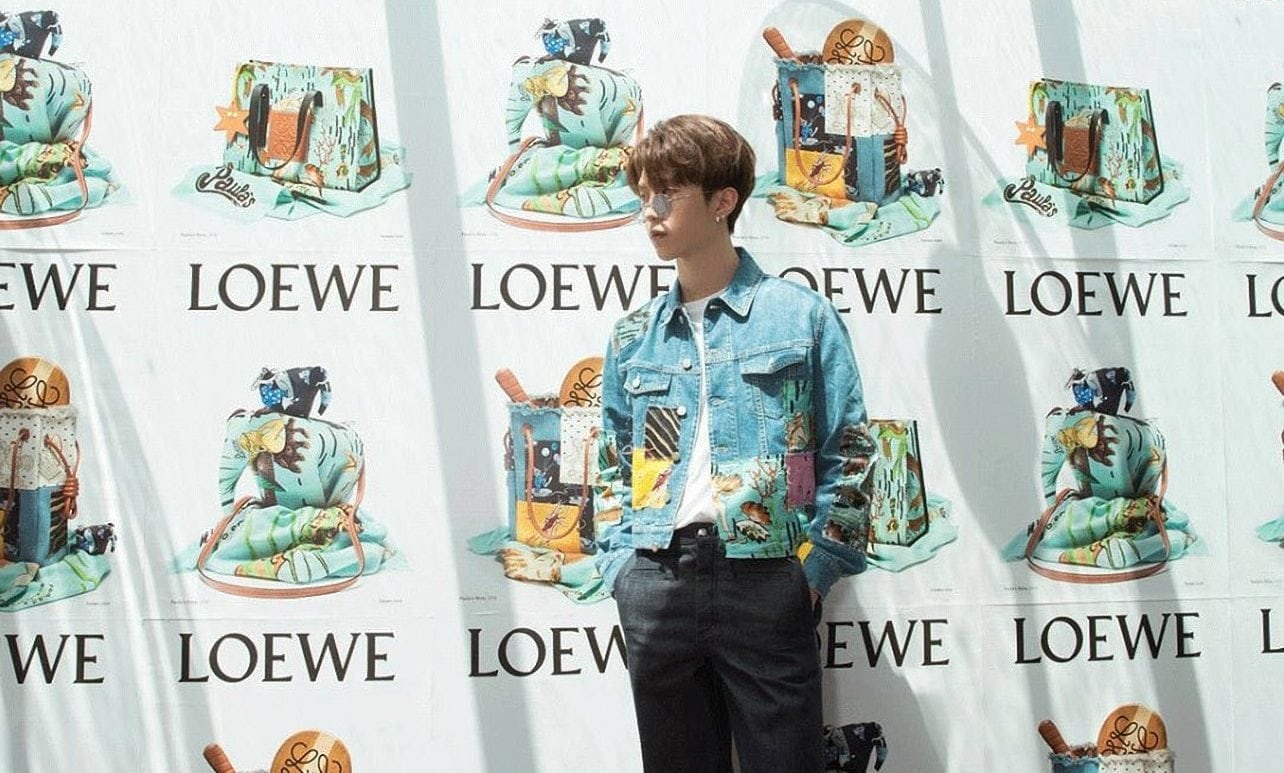

Over the past two months, there has been no escaping Wang Ju’s name on Chinese social media. A contestant on China’s trending talent show Producer 101 China (创造101), Wang Ju immediately found controversy because of her diva-like charisma on stage. Compared to the typical pale-skinned, sweet-looking pop-star wannabes she competed against, Wang was completely different: dark-skinned, outwardly ambitious, and fiercely independent. In short, she was everything a supposedly desirable Chinese lady wasn’t.

Her memorable interviews from “Producer 101” quickly made her an idol to Chinese women who shared her modern sensibility. Wang turns memorable phrases regularly, like, “the motto of my high school is the word ‘independence.’ Being mentally and financially independent is also my life motto,” and “Wang Ju Quotes” have spread rapidly via different memes across the Internet. She’s connected with China’s growing community of young, highly educated urban women—a female archetype seldom seen in Chinese media.

China’s #MeToo Movement#

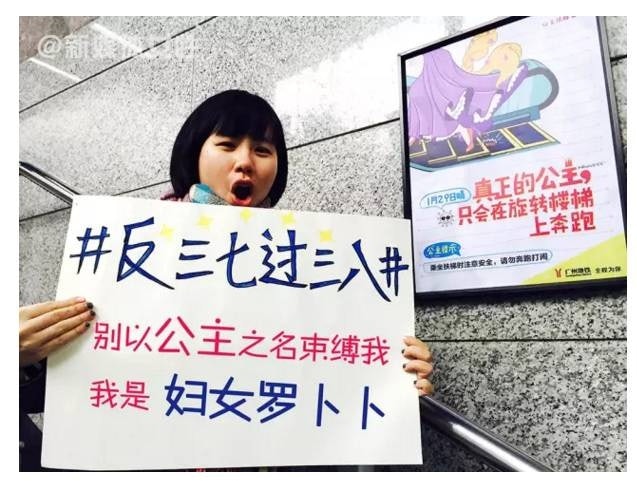

Gender inequality has always been a difficult and embarrassing topic for Chinese women to speak out about. However, the recent emergence of “China’s #MeToo Movement,” which caught on after the U.S. movement, has broken that long silence. Protests have mounted against many Chinese gender norms, such as the March 7th holiday ‘Girls Day’—a day that celebrates young, unwed girls (while also separating them from married women for prospective suitors.) During the holiday, ads often encourage women to look more “girly”, or in other words, more conventionally attractive to men. But lately, women have promoted an alternative: ‘Women’s Day’ on March 8th.

It’s a ploy that’s gaining momentum. On the social media site Weibo, the hashtag #反三七过三八# (#No to Girl’s Day, Yes to Women’s Day#) has generated more than a hundred million views and 80 thousand opinion posts. It’s a place where Chinese women can commiserate over their country’s traditional gender roles and the mainstream ads that won’t stop reinforcing them.

It seems logical then to think that more empowering ads for Chinese women would succeed—if done correctly. Today’s new urban, professional demographic of Chinese women are put off by airbrushed and carefully staged illusions of beauty, so a brand that can skillfully convey a more purposeful gender message could win hearts and minds.

SK-II Bare Skin Project#

SK-II is one brand that stands on the leading edge of gender-positive advertising. The facial care company sparked gender conversations in China in 2016 with their campaign film addressing “leftover women” or Sheng nu. This year, SK-II launched the “Bare Skin Project”—a social media campaign that exposed their brand ambassadors without makeup to encourage women to love their natural look. The Weibo tag #skii我行我素# (#skii DoItMyOwnWay# ) has become a popular online locale where women can post their natural selfies and statements of self-love.

Chow Tai Fook: “Character of 2017” Survey#

Even luxury jewelry brands, which traditionally rely on romantic partnerships for sales, are trying a different approach in a more gender-positive climate. Chow Tai Fook recently came up with the initiative “Character of 2017”, which asked women on social media sites how they would best represent their 2017 selves in one Chinese character. Frequently mentioned characters included “fun趣”, “love爱”, and “change变”, and “love爱” eventually won the popular survey, prompting discussions about the different types of love with women.

Takeaways#

From these two refreshing examples of luxury marketing to Chinese women, here are the lessons to learn:

- Gender positive messages do resonate but to a targeted group. It is true that mainstream standards in China still prefers the wanghong-style pretty. But more and more, urban and highly educated women are in need of a fresher, more empowered narrative.

- Tell a China-relevant story. Many international brands that sell body positive messages in China have simply “localized” their global brief, which doesn’t adequately represent what Chinese women are facing. An irrelevant story will not resonate.

- Be ready for opinion backlash. In such divided times, you can't win them all. Instead of playing in the middle to please the masses, brands should take a strong stance to inspire and resonate with the right target.