“As I’ve grown older, I’ve started to invest more money into skincare than designer bags,” said Linda Zhong, a 24-year-old live-streaming hostess in Shenzhen, China. After a rough calculation, she estimated her monthly skincare budget at around 10k RMB (1,488). “Skincare is the most rational investment a woman can make to herself,” she added.

Half of that hefty budget goes into her daily beauty regimen, which starts with Skin Caviar Luxe Cream (505/50ml) from the Swiss brand La Prairie, in the morning, and a skin-smoothing laser, Iluminage Touch, from Israeli brand Iluminage (587), before bedtime. But even this sophisticated combo of luxe products and black-tech beauty devices no longer suffice. Last year, she hired a Korean skin coach, located in a local upscale skincare management clinic, for more professional advice. Now, twice a month, she checks in with her coach for a suggested treatment based on her skin condition, be it 24k Gold Facial from the Japanese brand, SIRRAH (156) or Diamond Peel from French luxe brand, Chantecaille (200).

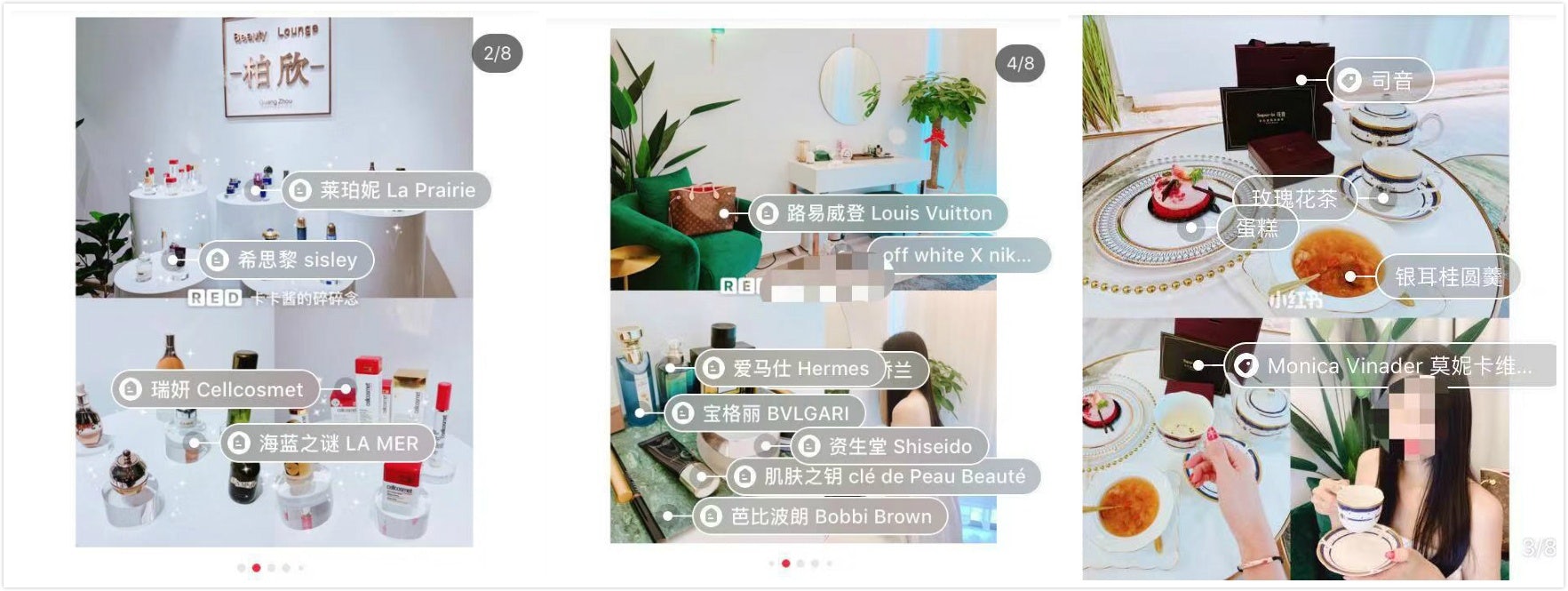

In millennial China, Linda is hardly alone in being young, but spending hugely on skincare. More and more Chinese young women are flocking into skin management clinics for pro-level coaching on beauty supplements, injectable Botox or fillers, and holistic nutrition. "The skin management industry is in a state of blowout since 2016. There are more than 1,000 skin management clinics in the city of Wuhan alone," Wang Wenle, secretary-general of the National Office of skin managers, told Chinese news portal Jiemian during an interview. Marketed as being different from traditional beauty salons, these skin management clinics appoint Korea-trained dermatologists to analyze your face, tailor an anti-aging treatment package, and coach you on future steps for prettier, more youthful skin (which often means cosmetic surgery). On the lifestyle platform, Little Red Book, more than 70k experience-sharing posts are written with the hashtag “skin management.” It’s not an exaggeration to say that skin is a serious business in China today.

The Chinese fanaticism for perfect skin feels more prevalent now more than ever, as spending on skin improvement products and procedures has risen to previously unthinkable levels. In the West, such investments are usually limited to a select group of wealthy, high-maintenance women. Yet, in the urban, middle-class of China, it’s a mainstream practice. And while there is no singular truth to Chinese women’s skincare obsession, there are three major cultural motives shared by many.

First, the idea of looking eternally young has a particularly strong tie to personal success in China. Different than the global marketing narrative of “embrace your age,” the Chinese narrative wants a woman to look like an 18-year-old girl regardless of her actual age. In fact, the more a woman can conceal her age via skincare, the more successful she’s perceived to be. Fashion magazines and TV shows continue to glorify mature women with overdone cheeks for being “冻龄女神”, translated as an age-freezing goddess — a euphemism for a “good example” of the type of woman who looks much younger than her age. “I go to regular coaching in skincare clinics not because I am narcissistic,” says Cynthia Zhang, a 27-year-old investment banker based in Hong Kong, described a woman’s face as her most important social capital. “I go because being beautiful makes my husband proud and gives him mianzi among his friends.”

Second, perfect skin is what people only get to see in social media today. The prevalence of beauty filters has made it believable that perfect is the new normal, magnifying the already-existing obsession with flawless face. Last week, Spain-based retailer Zara featured a non-filtered model, Jingwen Li, in a campaign, where the model’s freckles upset many Chinese netizens. Freckles, just like other natural skin defects, do not meet the modern Chinese definition of beauty. As a result, many regarded Zara’s choice as a racially discriminative portrait of Asian women. When Zara later explained the campaign as being “non-processed” and aesthetically dictated by “a different Spanish beauty standard,” the following discussion on Weibo showed that the brand’s no-filter attitude had shocked many. In China, posting a non-filtered group photo in WeChat Moments could be perceived as committing social suicide. In an age when people heavily consume carefully filtered social selfies and influencer content, even the slightest skin imperfection could stir public discomfort. Call it an unrealistic expectation, but the over-polished airbrushed beauty standard is here to stay.

Third, but most importantly, having a youthfully pretty face is still unabashedly seen as a legitimate way to get ahead in life. Linda, the live-streaming hostess, told Jing Daily, “I invest in my looks because my face gives me many benefits. Once I went to the hospital and forgot to take my purse with me, and the person behind me in the line offered to pay for my registered fee. Plus, guys in parties notice me first.” Besides the day-to-day benefits, looking pretty also gets Chinese women more advances in life’s bigger questions. “(The skincare’s) largest audience is Chinese women in their golden career age from 22 to 33. Because having a pretty face is having a successful image, it helps people advance in career, love, family, and friendship,” said Gordon Niu, manager of Walkin International, a beauty e-commerce management firm in Asia Pacific. Certainly different than the global #MeToo and #Time's Up environment, but it’s still politically correct for Chinese women to openly leverage her good looks as social capital to get a higher salary, a successful husband, and more digital attention that could turn into influencer dollars. Thus, the investment in perfect skin is not only an aesthetic choice, but also a coldly realistic one.

Despite the surge of feminist ads in recent years, the Chinese attitude towards women aging remains hostile. The mentality of “aging means losing to women” sadly still prevails. Until a radical cultural movement shakes things up, many other investment forms, such as skin-management, are likely to take place.