Key Takeaways#

:

In 2019, mainland Chinese consumers accounted for around 40 percent of global luxury sales and the bulk of growth. So the question is: Who are the next Chinese? The answer is more Chinese.

The Japanese market looks fully mature, even though there is a “silver consumer lining.” Meanwhile, the South Korean market did well in 2020, but can only do so much.

Southeast Asian shoppers and Indian consumers will help move the needle in luxury but in the next generation, not the next year.

According to the Brookings Institution, in 1950, more than 90 percent of the global middle-class lived in Europe and North America. Today, more than 20 percent reside in China, and that should go up to 25 percent by 2027, or a total of 1.2 billion potential consumers.

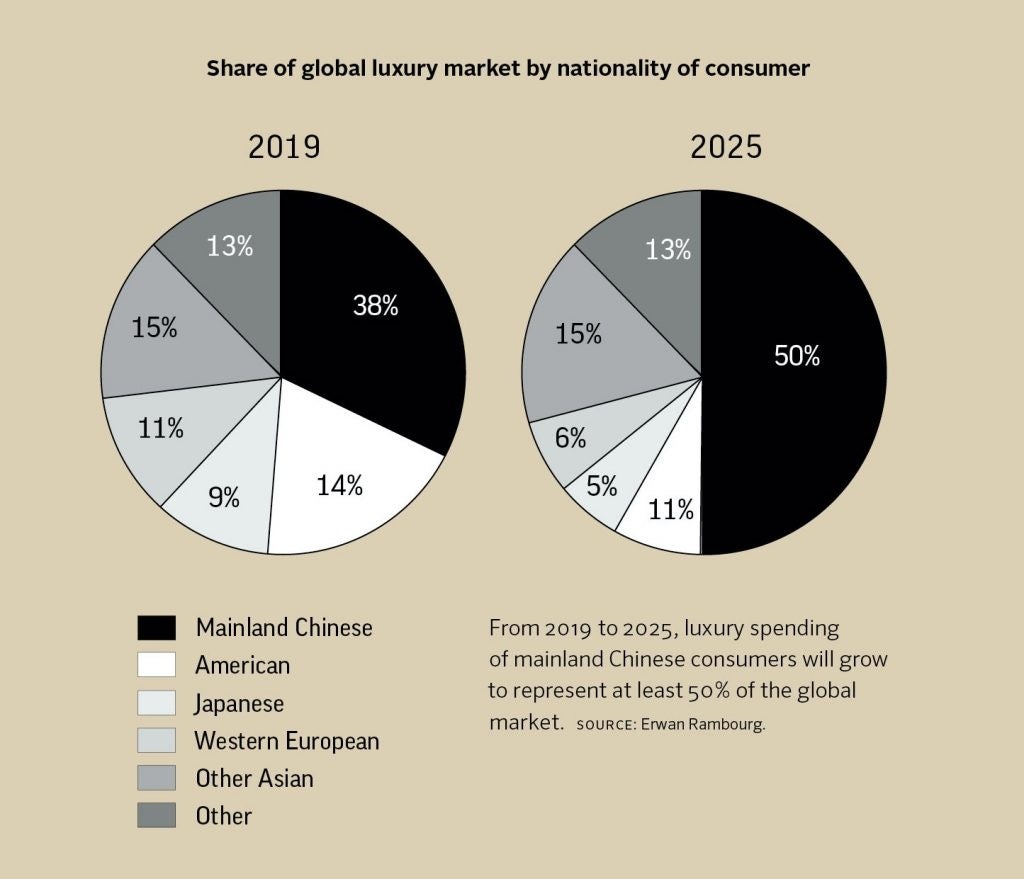

Now, not all of them will be purchasing luxury products. But, as I explain in my book Future Luxe, Mainland Chinese should jump from 38 percent of personal luxury sales in 2019 to 50 percent or more by 2025. Most brands will be seeing their sales to China more than double in that timeframe.

But can other nationalities in Asia significantly move the needle for luxury companies during that period? I doubt it. The contribution of the Japanese, for example, could drop from 9 to 5 percent, while all other Asian nationalities could roughly contribute 15 percent of sales over the period.

The Japanese were the key luxury consumers twenty years ago and accounted for more than half of Louis Vuitton sales as late as 2003. But with Japan’s aging population (its predominantly young female luxury consumers are not being replaced), the long-term prospects do not seem positive.

However, there are two reasons for optimism about Japan in the short term. First, this is a country where female labor participation has ramped up dramatically since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Womenomics policy kicked in. That is a direct consequence of muted immigration and an aging workforce (which should translate into some wealth creation).

Second, retirees are leaving work with relatively high amounts of money, and many do not have children to pass it on to. Therefore, they might as well spend it on themselves. Both realities likely explain why the Japanese luxury demand was stronger than expected in 2018 and 2019 and why it could still be somewhat robust in a post-COVID world. I would expect this growth to be pedestrian, though.

In South Korea, the cosmetics market has been very well supported. But some potential for growth in the luxury market remains, particularly with the emergence of male consumers who are gaining interest. South Korea is perhaps the only country where male-driven luxury consumption could outpace female growth over the next decade.

Alongside Mainland China, South Korea did well in terms of luxury sales in 2020 on the back of the repatriation of growth. But, there was also resilience linked to the fact that its citizens were not hit as hard by COVID-19 as others, and the country managed the crisis very well.

In Southeast Asia, real hopes exist for luxury because Vietnamese consumers already have a strong influence on imported spirits like cognac and scotch. Meanwhile, Indonesia boasts a dynamic and youthful population. The issue is that the upper-middle class in those countries cannot compare to China’s. And while growth potential might be there, it isn’t likely to move the needle for some time.

In India, meaningful luxury growth among high-end consumers remains wishful thinking. Obstacles for the sector have included insufficient wealth, import tax difficulties, unorganized retail, and fundamentally different consumer tastes, which tend to focus on the intrinsic value of products rather than branding.

Fifteen years ago, I started writing a report called Big Bang Galore? Can Luxury Make It Big in India? I never ended up publishing it because I thought we had time before investors would take notice. Fifteen years later, nothing has changed much. However, a glimmer of hope has appeared.

First-generation wealth (as opposed to inherited wealth) is emerging, and it will likely want to be noticed. Indian consumers may well help support growth in the sector once China starts to plateau, and I see this happening gradually over the next ten years. But for now, luxury's next China is more China.

Erwan Rambourg has been a top-ranked analyst covering the luxury and sporting goods sectors. After eight years as a Marketing Manager in the luxury industry, notably for LVMH and Richemont, he is now a Managing Director and Global Head of Consumer & Retail equity research. He is also the author of Future Luxe: What’s Ahead for the Business of Luxury (2020) and The Bling Dynasty: Why the Reign of Chinese Luxury Shoppers Has Only Just Begun (2014).