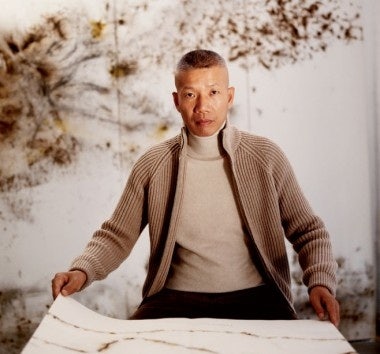

In Interview, Chinese Contemporary Artist Discusses New Exhibition, World Expo, Family#

Fame has done nothing to slow Cai Guo-Qiang, one of China's most respected and prolific contemporary artists. Last month, as Jing Daily reported, Cai held a fundraising auction in Beijing, which included works by Cai, Sui Jianguo, Zeng Fanzhi and others and raised nearly $500,000 for Haiti earthquake relief. Also in March, it was announced that Cai will be the first artist to hold a solo exhibition at the completely renovated Shanghai Bund Art Museum, with his all-new "Peasant Da Vincis" exhibition set to open on May 4.

This week, Cai spoke to a reporter from China's First Financial Daily (第一财经) about his new exhibition, the current state of Chinese culture, and his family. According to the article, in preparation for the exhibition Cai spent six years traveling in some of China's most remote areas to collect over 60 homemade inventions from 12 farmers ("peasants"). Recently, some of these farmers have gotten the attention of domestic Chinese and foreign media for their "shanzhai" -- or “knockoff" -- helicopters, robots, and mobile phones.

As Cai tells the newspaper, although the farmers and migrant workers whose works comprise "Peasant Da Vincis" are often looked down upon by China's elite, he feels that they are true artists, and embody the spirit of tinkering and invention seen in historical figures like Leonardo da Vinci.

From the interview (translation by Jing Daily team):

First Financial Daily (FFD)

: Artists generally like to pursue vagueness and uncertainty [in their work]. Are you the same way?

Cai Guo-Qiang (CGQ)

: Personally, I like some things to be accidental and hard to control. Uncertainty has a certain allure to me. In ["Peasant Da Vincis"], I allowed myself a certain ambiguity, not only in terms of being an artist, but also as a curator and a collector. Actually, this exhibition is like a direct descendant of my gunpowder art, and in a way calls back to my childhood interests. As a child, I used to dream about tinkering around with these kinds of handicrafts. I don't try to cover up my immaturity -- I actually enjoy my immaturity. In a way, I've always maintained a sort of childishness.

FFD

: Some people have questioned whether [you] take advantage of your official standing to freely make works that other artists would have no way of making; In this new exhibition, you look at the status of farmers, so is this a response to these comments?

CGQ

: I can't really respond to that. Every person is free to question me. No matter how I make things, there will always be people who question it. From the Shanghai APEC fireworks show in 2001 to the "big footprints" at the Beijing Olympics opening ceremony that gave people a deep impression, to the 60th anniversary National Day "Peace Doves" and "Net Curtain Fireworks," all of [these projects] were "Official Works."

I spend virtually every day developing large-scale programs that have to do with big cities, they're very distant from the countryside. That gives me a skewed perception. This time, my works are helping me make progress on a personal level, [so] I'm trying to keep my distance from the Shanghai World Expo.

Regarding the issue of [my] status, actually in our country, we just have the government's efforts to reflect the mainstream concept of happiness. Official status helps intellectuals of our generation to do things for individuals, to do things for the country, and without the governmental [nod] it's hard to address the concerns of farmers, and individual concerns.

FFD

: You and Xu Bing, along with other returned overseas artist, chose to return to China to proceed with your artwork. Is this because of the current art market?

CGQ

: I have limited capabilities. In terms of making my works, I can't overthink them or they just seem unimaginative. To be honest, artists of our generation who left, then came back to, China have very strong feelings towards Chinese culture. We're really dependent on it. And it's undeniable that Chinese culture has a lot of problems right now, but I'm still confident.

I feel that I'm not really a "returnee" -- I actually never really left. Asian philosophy has a very strong sense of inclusiveness, but the era of inclusiveness has changed, and also the idea of inclusiveness is in itself somewhat contradictory. The West has resolved this contradiction, to the point where artists have high achievements, whereas in the East these contradictions are presented to us without any solutions. I use artwork to express these contradictions, express the vacillations between East and West, between Left and Right.

FFD

: What has had the biggest influence on your artwork?

CGQ

: The socialist and communist methods of propaganda have had a huge impact on me. What they brought is a kind of artistic methodology, whereby the profound philosophical principles of Marxism or Leninism were understandable to farmers. I am making new work that looks at this aspect. Actually, it came quite naturally to me. I was actually already moving in that direction.

FFD

: Have your daughters had an influence on your artwork? Have you made any works specifically for your daughters?

CGQ

: I make everything for my daughters. My wife and I have a 20 year old daughter and a 6 year old daughter. For the last 20 years, every day I've been telling my eldest daughter a story, "Little Fish DuDu and her backpack," a sort of adventure about a girl's life. It's kind of like a regular TV series starring this character I created for my daughter, and both of them appreciate the imagination of this story. However, after 20 years, it's getting harder and harder to tell.

My 20 year old has started to make art herself, but now she's got two pretty difficult mountains to cross: one is art itself, and the other is me.