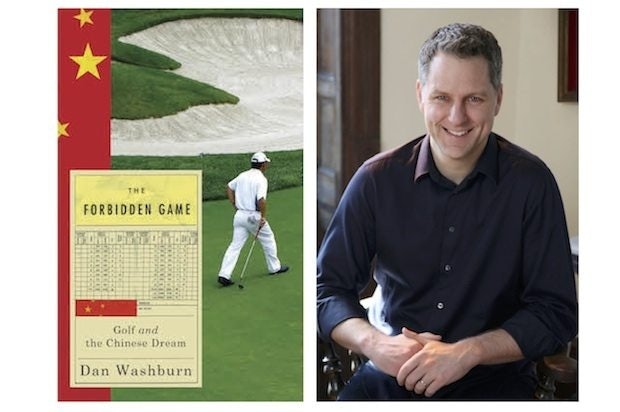

The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream (L) by Dan Washburn (R) tells the story of the unpredictable rise of golf in China.

In China, many industries are illegal, yet highly lucrative: prostitution, narcotics, counterfeit goods, and—surprisingly for many Westerners—golf. With the nickname “green opium,” the preppy sport’s volatile rise alongside China’s rapid economic growth has been the subject of years of research for Dan Washburn, author of the newly published book The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream.

First outlawed by the new Chinese Communist government in 1949 for being too bourgeois, golf began its ascent in the country when it was legalized in 1984 as China pursued its reform and opening up policy. After construction of new courses began to take off as golf became popular with China’s ultra-wealthy, the Chinese government abruptly prohibited all new courses in 2004 on the basis that they were taking up too much of the country’s vitally important land resources. Thanks to a lack of enforcement and ease in bribing local officials, the ban certainly hasn’t stopped the sport from taking off: developers have tripled the country’s total number of golf courses since the start of the policy.

The Forbidden Game not only tells the story of the rise of golf in China, but also one of the human experience behind China’s quickly expanding economy. The book follows three characters realizing their own version of the “Chinese Dream” through the golf industry: Zhou Xunshu, a rural villager who rises to the ranks of China’s growing middle class through a professional golf career, Wang Libo, a lychee farmer who becomes a shop owner when his village’s land is seized for the massive Mission Hills complex in Hainan, and Martin Moore, a golf course developer from the United States who cashes in on China’s golf boom when the American Dream fails him.

Their stories show that China's economic development is rife with growing pains—Zhou spends years struggling to make ends meet on the new and poorly organized pro golf competition circuit, Wang represents millions of peasants victimized by land grabs who often receive far below market value for their property, and Moore learns to navigate the tumultuous business environment in China’s golf industry, complete with corrupt officials and Thai mafia members.

In order to learn more about how this banned business can be so lucrative in China—and what it says about the country’s economic rise—we caught up with Washburn for an interview on his book and what’s next for the Chinese golf industry.

The book focuses on three main characters: Martin, an American golf course construction executive in China; Zhou, a professional Chinese golfer; and Wang, a Hainan lychee farmer whose land is confiscated for golf course construction. Why did you choose these particular stories?#

The story of golf in China is so complex and touches on so many different aspects of life in modern China, that I thought I needed multiple storylines to do the topic justice. Zhou, Wang, and Martin all occupy very different places in China’s unique golf environment, but they are all hard workers and I think they are easy to root for. Zhou’s inspiring story—he goes from peasant farmer to security guard to pro golfer—accentuates the divide between urban and rural China and he’s also a symbol of the country’s emerging middle class. Wang shows how easily rural lives can be uprooted by China’s breakneck development, but he’s also an adaptable survivor, an example of the great entrepreneurial spirit that exists in so many Chinese. And Martin’s an intelligent pragmatist, the perfect guide for navigating China’s byzantine political and business landscape. He offers an exclusive ground-level view—literally—of how things get done in China. I find it interesting that all three men ended up where they were by accident. Zhou never knew golf existed until he became a security guard at a golf course. Wang was rolling along as a self-employed taxi driver when he learned a mega golf development was moving in next door. And Martin never wanted to work in China at all. In fact, his colleagues thought he was crazy for taking a job there back in the 1990s—now, those same people are knocking on his door seeing if he has any work for them in China.

Peasant-turned-pro golfer Zhou Xunshu competes at the China Tour. (Dan Washburn)

What can we learn about the "Chinese Dream" from China's golf industry?#

I think the very fact that a golf industry exists in China is a sign that the Chinese Dream is alive and well for some. There are few things more aspirational in nature than golf in China. It’s so costly to play the game, so expensive to purchase a home near a course, that the activity and the life that surrounds it has become as much a symbol of “making it” in China as a Louis Vuitton handbag or an Audi A6. But I think the larger world surrounding the game shows that the Chinese Dream means different things to different people. Very few can afford the mansion with the fairway view or even the golf club membership. For Zhou, golf allowed him to simply dream of a better life beyond his village or workers dorm. For Wang, although he may have felt forced to sell his land to a golf development, the money he made from the transaction allowed him to dream of a better future for his children in a time a great uncertainty for so many others—a sign that the Chinese Dream is not yet attainable for all.

In the book, golfer Zhou Xunshu and his peers face many struggles on the domestic competition circuit, yet Chinese pros such as Feng Shanshan and Guan Tianlang have been seeing major international success in recent years at tournaments such as the LPGA and US Masters championships. How are some able to reach this level of success despite the challenges in China's professional golf environment?#

It’s all about money. China’s domestic tours are not yet seen as springboards to international stardom, so those golfers with means pay to train and compete abroad. Most of this new generation of Chinese golfers come from money, have played golf from a young age, and have had access to top-level coaching most of their lives. That’s the exact opposite of Zhou Xunshu and his generation of blue-collar golf pros. For them, the domestic tour was the only outlet available to them, and they were thankful to have it—they needed an outlet to compete. The latest iteration, the PGA Tour China Series which launched this year, could be seen as a step forward for Chinese golf—it has brand recognition and a more international flavor. But guys like Zhou, the self-taught coachless pros, are finding it harder and harder to compete.

The world's largest putting course at Mission Hills in Hainan. (Dan Washburn)

New golf courses are often accompanied by the construction of luxury homes in China. Do you think most courses are being built to offer a high-quality playing experience or just to raise the value of nearby real estate?#

I think you’d have to say both. Most of the top course architects in the world are working in China now—because there are few jobs available anywhere else—and they take their jobs very seriously. I’m no golf course critic, but I do believe more and more Chinese courses are starting to gain international attention. But it’s also true that very few, if any, of them exist because of golf alone. It’s still the case that the only way a golf course in China can make a developer money is if it helps sell real estate. No one is making money just from golf in China.

The Chinese government’s reasons for the ban on new golf courses state that construction uses up too much land and that villagers' lands have been illegally confiscated. How serious are these problems?#

The problems are very serious. You’ve got 1.4 billion mouths to feed and limited water and arable land. I write in the book that the number of local-government-approved land-grabs in rural China has increased markedly since 2005, with nearly half of the country’s villages affected in some way. And of the 187,000 mass demonstrations reported in China in 2010, 65 percent were related to disputes over land. An estimated 4 million rural inhabitants in China have their land taken by the government each year, and the compensation they receive is far below market value. It’s important, however, to note that golf development accounts for only a tiny sliver of this, but it gets headlines because of its reputation as an elitist foreign import—some even call it “green opium.”

Workers dig irrigation trenches for a new golf course in Hainan. (Dan Washburn)

The book discusses how golf course construction was able to flourish despite the moratorium. Since Xi Jinping came into power, how has China's anti-corruption campaign affected the golf course building boom?#

It may have affected it a bit—things don’t seem to be booming quite as much as they were four or five years ago. But golf courses are still finding a way to get built in China, more so than anywhere else in the world. It will always be an unpredictable market (recent crackdowns are proof of this) until the central government realizes that some golf growth is inevitable and they decide to legitimize and regulate course construction. Ironically, many in the industry were cautiously optimistic when they heard Xi was next in line for the top job—he’s rumored to be a golfer—but not much has changed.

Golf is primarily a sport for the ultra-wealthy in China at the moment. Will it ever become more available to the country's middle class?#

Not in the foreseeable future. Everything about golf in China is expensive, and that all starts with the land the courses are built on. For a developer to make money on a course, they have to be able to sell real estate alongside it. And those who buy those houses want their communities to be exclusive, so greens fees remain high. There are no truly public courses in China—it’s all private or semi-private clubs. And since golf remains a politically taboo topic, I just don’t see municipal courses in China’s near future. Driving ranges may be the key to reaching a broader audience. Golf will likely always be a niche sport in China, but with 1.4 billion people, a niche there can still mean millions of people.

Buy The Forbidden Game on Amazon or visit the book's website for more ways to purchase.