Works Getting Harder To Source#

One of the recurring questions raised by some art market commentators over the past week, fueled by recent comments by auction house China Guardian and ArtTactic's latest report, is whether the Chinese art market is in "free-fall." ArtTactic's report, released last week, indicated that this spring's auction results at the "Big Four" -- Christie's, Sotheby's, China Guardian and Poly -- showed a 32 percent decrease from autumn 2011 and 43 percent decrease from spring 2011. Among the four, China Guardian saw the largest drop in sales, with 45 percent lower volume this spring compared to last autumn. Itself seeing a 39 percent decrease in overall sales this spring, Beijing Poly recorded the highest Chinese art sales, totaling US$485 million, a 36 percent advantage over Christie's.

In response to ArtTactic's report, coverage has ranged from introspective to over-the-top. Art Radar (accurately) noted, "Though the sell-through rate for Sotheby’s and Christie’s spring auctions were relatively high, Asian modern works clearly outnumbered and outsold contemporary. The flight to more established artists may be a result of collectors shifting their art investments to works with greater longevity and less risk exposure." Yet, showing a misreading of the current state of the Chinese art auction market, Abigail Esman wrote in Forbes that the market is in poor shape for three reasons: 1.) Chinese buyers were not out in force at Art Basel this year; 2.) Prices are stabilizing and "the real demand for Chinese Contemporary remains domestic"; and 3.) Works sold at auction have gone unpaid-for.

The Chinese art market is undoubtedly changing, and moving beyond from the massive price boom we saw in early 2011. But as Jing Daily wrote this January, this is probably a good thing for the state of the market:

[A]ny slowdown that may occur this year [in Asia] could be a good thing to prevent overheating and cultivate healthier markets. This could be particularly true in countries like China, where domestic auction houses like China Guardian and Beijing Poly have seen an influx of hot money drive prices for less established Chinese artists to unsustainable levels.

Still, for all the chatter about Asia’s art market possibly losing steam in 2012, a significant drop-off seems highly unlikely, particularly in China. The most pronounced trend recently taking shape among Chinese collectors — both new and established — is bidding for the best works by blue-chip Chinese contemporary artists, while remaining cool towards sub-par works.

Addressing the lower turnover for "the big four" auction houses in the Chinese art segment, it is important to put why volumes, and overall sales figures, are lower into context. A few important points come into play here. One, sell-through rates remain comparatively high, which indicates that either there are fewer marquee works up for auction that are attracting frenzied bidding, or there are fewer works up for auction overall. Since the spring 2011 boom, when "the big four" was comparatively flush with inventory, with auctions packed with rare and particularly valuable works by top blue-chip artists, and many Chinese collectors were just starting to enter the market, both have become true. Quite simply, many of the most historical and best-quality works -- especially in the contemporary Chinese art segment -- have been sold, and those buyers are hanging onto them rather than looking to quickly "flip" them at auction.

This is true in the (still-buoyant) modern segment as well. Following three auction seasons packed with artists like

Qi Baishi#

,

Sanyu#

and

Zhang Daqian#

, scarcity is rearing its head. Already, we can see Chinese auction houses having a more difficult time procuring the works that Chinese collectors want — hence, China Guardian and Poly have been busy over the past nine months holding sourcing events in Australia and the United States to purchase rare art & antiques they can sell back in China. This also partly explains why Chinese bidders have turned in such a strong way to

Li Keran#

-- a known artist before this year, of course, but not one whose work regularly sold for US$46 million: blue-chip modern artists are becoming harder to find, and harder to get.

To address the points raised in the Forbes article, first:

Chinese buyers have yet to become a significant buyer base for Western art, period#

-- it's not just at Art Basel. Major dealers have invested heavily in opening outposts in Hong Kong, and taken some of their best Western art to fairs like ART HK, in recent years in an attempt to cultivate that base, but it has yet to pay off. Selling non-Chinese art to the emerging Chinese collector class will have to be a long-term strategy. This is one of the distinguishing factors of the art market in China: it remains mostly made up of newer collectors, who start off with buying what they know -- which, typically, is Chinese art. (Whether that's centuries-old calligraphy or modern or contemporary art.) In this way, it can be said that China's collectors remain broadly "nationalistic," with few knowledgeable enough about collecting Western artwork to make a major impact. Aside from Picasso's “Femme Lisant (Deux Personnages),” purchased by a Chinese collector for $21.3 million in 2011, few high-profile Western works have gone to Chinese buyers. As such, it's not surprising that Chinese buyers were not out in force at this year's Art Basel -- they never are.

Second, the article holds that the Chinese art market is in trouble because "the real demand for Chinese Contemporary remains domestic," and prices are not skyrocketing as they did in spring 2011. What the article does not point out is that, since the depths of the global financial crisis in 2009,

the primary demand for Chinese art (modern, contemporary or otherwise) has been domestic, since Western collectors either cut down on their Asian art buying or sold their Chinese art#

as a surging new collector class emerged. As Jing Daily mentioned in our article on the positives of a slowdown in the Chinese art world, were art prices in the contemporary Chinese segment to continue leaping as they did between autumn 2010 and spring 2011, art commentators would be voicing bubble fears -- as such, a stabilization of prices is exactly what the market needs. To single this out as a marker of doom is simply myopic.

Finally, to think that non-payment of work at auction by Chinese bidders is new, or that it does not happen elsewhere as well, indicates similar short-sightedness. While anybody following the art market -- and, most certainly, auction houses -- agrees that this is a problem, and is hurting the Asian art market,

concerns about Chinese non-payment at auction were being voiced as early as 2009#

, and even at the height of the market in 2011.

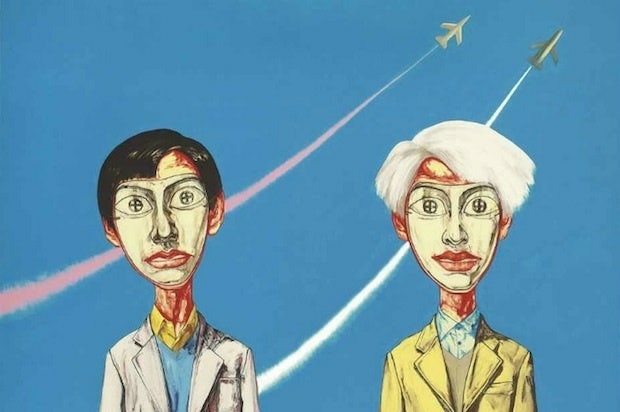

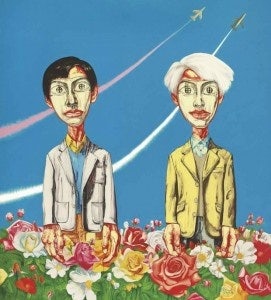

In short, the growing importance of the Chinese market to major auction houses, and its massive presence on the world stage means it is important to turn a critical eye to areas that deserve a closer look. But to understand where the Chinese art market is now, and how it got there, takes more than a few Google searches. Lower auction volumes and less dazzling auction totals may simply reflect a maturation of the young market; now that collectors are hanging onto their artwork for longer (rather than flipping them, speculator-style), we can expect to see volumes lower and fluctuations occurring. But at the same time, as work by the blue-chip contemporary Chinese artists of the 1990s becomes harder to come by, coming years will see the emergence of newer artists whose sales will pick up the slack. Still, it's difficult to argue that Chinese buyers have turned away from top-quality contemporary art when three paintings by blue-chip artist Zeng Fanzhi, formerly held in European collections, sold in Hong Kong to Chinese collectors earlier this month for a total of US$9.7 million, each surpassing high estimates. (His Mask Series from 2000 nearly tripled estimates.)

Everything, including the art market, is cyclical.