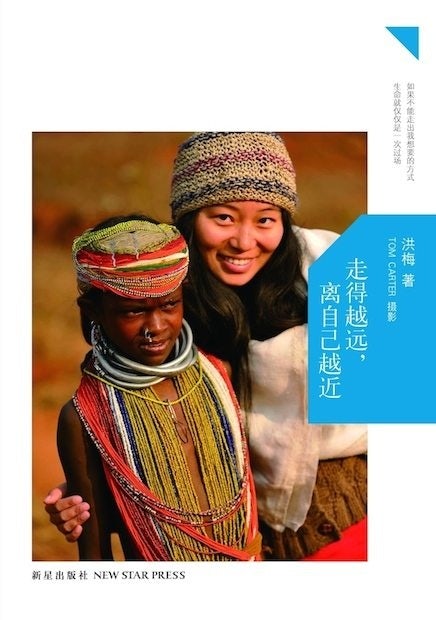

Travel writer Hong Mei. (Courtesy Photo)

For many of China’s new travelers heading abroad for the first time, a guided tour group focused mainly on shopping and sightseeing is a safe, reliable booking option in an unfamiliar country. As the Chinese travel market matures, however, seasoned vacationers are skipping the tour bus and opting for solo trips focused not just on shopping and landmarks, but also on new experiences and learning about local cultures. Even President Xi Jinping promoted this mindset last week in the Maldives when he advised Chinese travelers to “eat less instant noodles and more local seafood” when in other countries. As incomes in China rise, the length of travel is also increasing for some, and more Chinese travelers are even taking an entire “gap year” abroad.

Increasing interest in unique trips has fueled the growth of a genre of travel memoirs in China covering off-the-beaten-track adventures. Among authors in this category, Chinese adventure traveler Hong Mei (洪梅) had published perhaps one of the most unique titles to date about her year traveling in India, which has a surprisingly small number of Chinese visitors given its close proximity to China. Entitled The Farther I Walk, The Closer I Get To Me, her Chinese-language book recounts her trips to an extensive number of locations in India, including one Pakistan border region that had never issued a permit to a Chinese visitor.

In a recent interview with Hong, she talked to us about her thoughts on the popularity of adventure travel in China, the future prospects for a Chinese tourist boom in India, and differences in tastes between older and younger Chinese travelers.

A growing number of Chinese members of the middle class are taking “gap years” to travel abroad—how big is this trend and what is fueling it?#

China’s new “gap year” phenomena is the result of several big societal shifts that have occurred in our country [over] the past decade. Primarily, the newfound disposable income of the Chinese middle classes, access to information, and the opening of borders by favored nations who want a piece of our disposable income. What country wouldn’t want the revenue of 1.43 billion tourists?

Chinese “gap year” travelers are kind of revolutionizing our traditional ideas of travel by saying “We have the means and the money to travel abroad now. The world is ours!” Historically speaking, the Chinese have never really been interested in exploring the world before, so this really is a brand-new concept to us. But like everything in China nowadays, gap years among the middle class are more about being fashionable, simply making an appearance; their goal is to see as many countries as possible in as little time as possible. That is why there is a rivalry between Chinese gap year travelers and adventure travelers.

The cover of Hong Mei's travelogue, The Farther I Walk, The Closer I Get To Me. (走得越远,离自己越近). (Courtesy Photo)

We’ve been reading a lot about how more Chinese travelers are becoming interested in “adventure” travel like the trip you took. How big do you think this trend will get in the coming years?#

China has become the largest tourism source market in the world, but of course most Chinese tourists, even the gap year travelers, are NOT interested in adventure travel or hard-core backpacking. We Chinese like our trips abroad packaged, all nicely wrapped up in a designated “Golden Week.” We pose for pictures in front of the famous sites, we hop back on our buses with the other hundred Chinese tourists, then we go back to our hotels to eat instant noodles.

Adventure travel—that is, the idea of having to find our own way around a country without someone with a flag and megaphone leading us—is unheard of among older or wealthier Chinese. Only disenfranchised and directionless Chinese youth are daring to venture off the beaten path; it’s a kind of symbolism of our refusal to settle down in some meaningless job or allow our families to force us into an arranged marriage. And it is the youth whom have popularized adventure travel here, by writing and publishing books about their wild experiences abroad. These memoirs, including my India travelogue The Farther I Walk, The Closer I Get To Me (走得越远,离自己越近) are becoming best-sellers as the idea of “having an adventure” catches on. I think the world will soon be seeing more and more Chinese backpackers in its youth hostels (sorry about that, ha ha).

What inspired you to take this journey and choose an “off-the-beaten-path” approach as opposed to a more “typical” vacation?#

Having backpacked across all of China and all of India, I don’t think the beaten path is any way to travel. Travel is a chance to explore new lands and immerse yourself in a foreign culture. So why would anyone want to insulate themselves from those experience, which is basically what you are doing on a typical packaged holiday: you are paying to NOT experience life in the country you are traveling to.

In China, I spent a year sleeping on bus station floors and in cheap disgusting flop houses and traveling on the hard seat train or hitchhiking as I made my way around the 33 provinces. It was the first time I had been traveling, and it was a life-changing adventure that opened my eyes to my own country. I really don’t know any other way, so that’s why I took the same approach to India.

What were some of your most interesting experiences when traveling in India?#

India was my first time abroad, so you can imagine that everywhere and everything I experienced in India was interesting to me. And I think I was equally as interesting to India. Pretty much everywhere I went, the locals could not believe that I was a Chinese; they’d never seen a Chinese traveler before, they’d tell me. In Kutch (along the Indian-Pakistan border) I was the first-ever Chinese to be issued an official travel permit to that restricted region. I felt like I had made history.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced on the trip?#

The single biggest challenge was the visa issue. I was only issued two- or three-month visas at a time, so I kept having to leave India, which killed my budget. Most Chinese just go to India for a week-long holiday to the “Golden Triangle” tourist circuit, so the Indian embassy actually started becoming suspicious of me. They refused to believe I just wanted to spend a year backpacking across India simply because I love to travel. But that was in 2009; things are different now, and I expect visa regulations will ease as Sino-Indian ties improve.

India is quite close to China, yet it doesn’t seem to be a very popular destination for Chinese tourists compared to other countries in Asia. Why do you think this is and will it change in the future?#

Xi Jinping just visited India and announced a multi-billion-dollar investment in India’s railway. I think we’ll also be seeing more foreign direct investment between the two countries, and more cultural exchanges. Inevitably, China will grant India “Favored Nation Status” and then they will witness a surge of Chinese tourism to India. But prior to this new era of bilateral trade and tourism, India really hasn’t existed in the minds of we Chinese. Part of that has to do with our government not wanting us to be aware of India due to their historically cool political relationship. And the other part is China’s fixation on Western countries; we admire and aspire to be more like the developed West than the developing East, and India still has a ways to go before it can impress China enough to recognize it as an economic equal.